Learning Rust with Advent of Code - Day 6

Day 6

The problem: for a grid of 1000x1000 lights, you’re given a series of instructions to turn a range of lights on, turn them off, or toggle them.

Part 1: Implement the instructions, and count how many lights remain on at the end.

Part 2: Implement the instructions if lights are no longer binary but have integer-valued brightness, and count the total brightness at the end.

David

Attempt 0.0

Looking around online, I see that there is an Array2D crate, but I’m unsure what advantages it has over a normal, mutable 2D vector; when in doubt, I’ll stick with the baseline Rust code.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

use std::fs;

fn main() {

let file = "../Inputs/Day5Input.txt";

let input_raw: String = fs::read_to_string(file).unwrap();

let mut first_lights = [[0u1; 1000]; 1000];

first_lights[5][6] = 5;

println!("Position 5, 6 = {}", first_lights[5][6]);

}

1

2

3

Finished release [optimized] target(s) in 0.49s

Running `target/release/day_6`

Position 5, 6 = 5

A u8 is enough for part 1, and if a u1 existed, I’d use that instead; the lights can only have a binary value. I’ll switch to u16 for part 2.

Attempt 0.1

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

use std::fs;

fn main() {

let file = "../Inputs/Day5Input.txt";

let input_raw: String = fs::read_to_string(file).unwrap();

let mut first_lights = [[0u8; 1000]; 1000];

first_lights[5][6] = 5;

let mut sum: u64 = 0;

for row in &mut first_lights[..] {

for light in &mut row {

sum += *light;

}

}

println!("Total brightness = {}", sum);

}

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

error[E0277]: `[u8; 1000]` is not an iterator

for light in &mut row {

^^^^^^^^ borrow the array with `&` or call `.iter()` on it to iterate over it

= help: the trait `Iterator` is not implemented for `[u8; 1000]`

= note: arrays are not iterators, but slices like the following are: `&[1, 2, 3]`

= note: required because of the requirements on the impl of `Iterator` for `&mut [u8; 1000]`

So, it seems that the slice notation does indeed work, and calling a mutable reference on a slice seems to allow for the in-place modification of the object being sliced. What I forgot was that I also needed a mutable reference to a slice of row, because row is also a Vec.

Attempt 0.2

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

use std::fs;

fn main() {

let file = "../Inputs/Day5Input.txt";

let input_raw: String = fs::read_to_string(file).unwrap();

let mut first_lights = [[0u8; 1000]; 1000];

first_lights[5][6] = 5;

let mut sum: u64 = 0;

for row in &mut first_lights[..] {

for light in &mut row[..] {

sum += *light;

}

}

println!("Total brightness = {}", sum);

}

1

2

3

4

5

error[E0277]: cannot add-assign `u8` to `u64`

sum += *light;

^^ no implementation for `u64 += u8`

= help: the trait `AddAssign<u8>` is not implemented for `u64`

Okay, I forgot about how strict types are in Rust. Still, I now know a better option than TryInto, which was my old go-to.

Attempt 0.3

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

use std::fs;

fn main() {

let file = "../Inputs/Day5Input.txt";

let input_raw: String = fs::read_to_string(file).unwrap();

let mut first_lights = [[0u8; 1000]; 1000];

first_lights[5][6] = 5;

let mut sum: u64 = 0;

for row in &mut first_lights[..] {

for light in &mut row[..] {

sum += (*light as u64);

}

}

println!("Total brightness = {}", sum);

}

1

2

3

Finished release [optimized] target(s) in 0.23s

Running `target/release/day_6`

Total brightness = 5

Slicing works; let’s import the actual slice ranges we’ll need.

Attempt 0.4

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

use std::fs;

fn main() {

let file = "../Inputs/Day5Input.txt";

let input_raw: String = fs::read_to_string(file).unwrap();

let mut first_lights = [[0u16; 1000]; 1000];

for line in input_raw.lines() {

let mut tokens = line.split(|c| c == ' ' || c == ',');

let mut keyword = tokens.next().unwrap();

if keyword == "turn" {

keyword = tokens.next().unwrap();

};

let xmin: usize = tokens.next().unwrap().parse().unwrap();

let ymin: usize = tokens.next().unwrap().parse().unwrap();

tokens.next();

let xmax: usize = tokens.next().unwrap().parse().unwrap();

let ymax: usize = tokens.next().unwrap().parse().unwrap();

println!("{} {} {} {} {}",keyword,xmin,ymin,xmax,ymax)

}

let mut sum: u64 = 0;

for row in &mut first_lights[..] {

for light in &mut row[..] {

sum += *light as u64;

}

}

println!("Total brightness = {}", sum);

}

1

2

3

Finished release [optimized] target(s) in 0.36s

Running `target/release/day_6`

thread 'main' panicked at 'called `Option::unwrap()` on a `None` value', src/main.rs:15:41

So the very first token failed, before anything at all was printed. Each line is one of the following three types:

1

2

3

toggle 258,985 through 663,998

turn on 601,259 through 831,486

turn off 914,94 through 941,102

I’m splitting by either spaces or commas, and I take into account the different possible message lengths…but I’m not taking into account importing from yesterday’s input file rather than today’s. Oops.

But this is why Rust’s error messages are so useful. If all I knew was that the program failed at that line, I wouldn’t know why - but there’s no way that it could have returned None on my input after just one space, so I knew exactly where to look.

Attempt 0.5

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

use std::fs;

fn main() {

let file = "../Inputs/Day6Input.txt";

let input_raw: String = fs::read_to_string(file).unwrap();

let mut first_lights = [[0u16; 1000]; 1000];

for line in input_raw.lines() {

let mut tokens = line.split(|c| c == ' ' || c == ',');

let mut keyword = tokens.next().unwrap();

if keyword == "turn" {

keyword = tokens.next().unwrap();

};

let xmin: usize = tokens.next().unwrap().parse().unwrap();

let ymin: usize = tokens.next().unwrap().parse().unwrap();

tokens.next();

let xmax: usize = tokens.next().unwrap().parse().unwrap();

let ymax: usize = tokens.next().unwrap().parse().unwrap();

for row in &mut first_lights[xmin..=xmax] {

for light in &mut row[ymin..=ymax] {

*light = match keyword {

"on" => 1,

"off" => 0,

"toggle" => if *light == 1 {0} else {1},

_ => 0

}

}

}

}

let mut sum: u64 = 0;

for row in &mut first_lights[..] {

for light in &mut row[..] {

sum += *light as u64;

}

}

println!("Total brightness = {}", sum);

}

1

2

3

Finished release [optimized] target(s) in 0.39s

Running `target/release/day_6`

Total brightness = 569999

Star 1 acquired; now I just rinse and repeat for star 2.

Final Version

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

use std::fs;

use std::time::{Instant};

fn main() {

let start = Instant::now();

let file = "../Inputs/Day6Input.txt";

let input_raw: String = fs::read_to_string(file).unwrap();

let mut first_lights = [[0u16; 1000]; 1000];

let mut second_lights = [[0u16; 1000]; 1000];

for line in input_raw.lines() {

let mut tokens = line.split(|c| c == ' ' || c == ',');

let mut keyword = tokens.next().unwrap();

if keyword == "turn" {

keyword = tokens.next().unwrap();

};

let xmin: usize = tokens.next().unwrap().parse().unwrap();

let ymin: usize = tokens.next().unwrap().parse().unwrap();

tokens.next();

let xmax: usize = tokens.next().unwrap().parse().unwrap();

let ymax: usize = tokens.next().unwrap().parse().unwrap();

for row in &mut first_lights[xmin..=xmax] {

for light in &mut row[ymin..=ymax] {

*light = match keyword {

"on" => 1,

"off" => 0,

"toggle" => if *light == 1 {0} else {1},

_ => 0

}

}

}

for row in &mut second_lights[xmin..=xmax] {

for light in &mut row[ymin..=ymax] {

*light = match keyword {

"on" => *light + 1,

"off" => if *light <= 1 {0} else {*light - 1},

"toggle" => *light + 2,

_ => 0

}

}

}

}

let mut part1: u64 = 0;

for row in &mut first_lights[..] {

for light in &mut row[..] {

part1 += *light as u64;

}

}

let mut part2: u64 = 0;

for row in &mut second_lights[..] {

for light in &mut row[..] {

part2 += *light as u64;

}

}

let end = start.elapsed().as_micros();

println!("Part 1: {}", part1);

println!("Part 2: {}", part2);

println!("Time: {} μs", end);

}

1

2

3

Part 1: 569999

Part 2: 17836115

Time: 48406 μs

Part 2 complete! Fairly verbose - I’m sure there’s a more elegant way of applying a function to the interior of an array in Rust than the way I’m doing it - but not too bad in terms of readability. The runtime is not bad, either; there were twenty-three million assignments total for each part of my input, so a total time of 48 μs means that Rust is taking just over 1 nanosecond per assignment; without parallelizing, it’s hard to see how to beat that. Mathematica took 43 seconds, so a speedup this time of roughly 900x. Which is about consistent with my other comparisons so far for instances where Mathematica doesn’t have a built-in.

You might notice that I have &mut first_lights, &mut second_lights, and &mut row towards the end, in the summation loops. Those references certainly don’t need to be mutable, because I’m not altering the vectors at that point - but for some reason, I get a roughly 2% speed reduction by doing that instead of &first_lights etc. I have no idea why a mutable reference would be faster.

Felipe

Today we’re grapping with one of the most frustrating things in computer science. When you know there’s a better answer, but you just can’t reach it, despite your best efforts. Dave and I spent at least a month talking about pretty much every permutation of a solution, and prototyping various approaches. This problem is actually a great example of the type of problem where you can conceptualize it in a variety of ways, and try to solve it from different angles.

First, a disclaimer, the majority of the thrust of the thinking will be focused on part 1 of the problem, because we were confident a solution that solved p1 well could be adopted to p2. This is not necessarily true, but we were willing to accept a super elegant p1 and then think about how to solve p2 elegantly. With that out of the way, lets hop right in.

First, lets nail down the problem. It describes a grid, 1000 long, 1000 wide, in which each square contains a light. We want to toggle those lights on and off following a sequence of instructions. A few initial thoughts:

- Order matters, we can’t multithread the instructions.

- There’s probably an O(n) solution where we iterate over the instructions once.

- The O(n) solution is actually O(n*m), where m is the number of lights toggled in each instruction, unless we find a way to treat a set of instructions like a block.

- The easiest representation of this is probably an array of arrays, e.g. a matrix.

- A matrix opens the door to matrix algebra as a potential simplification.

- Dave’s favorite solution to simplify matrix problems is something known as a sparse matrix. We’ll probably have to at least try one.

The basic, O(n) solution (where n stands for the number of instructions), is the very basic brute force solution that we probably came to instinctually, namely to create an array of arrays initialized at 0 representing the grid, and execute every instruction in order. And that works, its a good solution, but the itch in my brain tells me we can do better.

Not just better, I believe we can create a soluton that works on a million by a million grid, with tens of thousands of instructions. That is really the goal here. To find a solution that doesn’t just solve the problem, but that solves the problem if it gets ridiculous.

Matrix Solutions

The first thing we discussed was removing redundant instructions. E.g. flipping a block that is already off doesn’t do anything… but scouting ahead to prune instructions adds complexity for not much gain, so that was right out. I wondered if given the nature of matrix algebra we could compress all the instructions into a single instruction which we would then execute as a final step to figure out the state of the grid. That seemed promising at first, since there’s a linear algebra crate that might do what we need.

Ok so that’s a promising opening, but one that fizzled out quickly. To represent a set of instructions as a matrix, we have to create an instruction matrix, and apply it on top of the previous instructions, which complexity wise, winds up taking just as long, or longer than applying the instructions to the grid directly. So that’s a no go. Which sort of knocks out matrix algebra a possibility. Thankfully, because I wasn’t exactly looking forward to the math.

So we probably don’t want to do linear algebra directly, but what about sparse matrices? I only happen to know they exist because Dave keeps evangelizing them to me, and this seems like a circumstance where it could be genuinely useful. What the heck is a sparse matrix though? And how would you discover they exist if you didn’t have Dave?

A sparse matrix is a data structure optimized for holding a matrix where most of the entries are 0 valued. That is, for example, if you had a 1000x1000 grid where only ten squares had non-zero values. Usually this is represented as a triplet structure, where we store a pair of coordinates and a value, but most programming languages have some kind of crate or module to represent these, and indeed, rust does too, so we don’t have to worry about how we would implement it ourselves, because we wont.

What if you’d never heard of a sparse matrix before? How would you arrive at something like this? The key is to think about two things.

- What data do I care about?

- Is there a data structure tuned for this data?

Point one you can answer pretty easily. You don’t care at all about anything flipped to zero, you only care about data in your matrix that is non-zero. That’s a bunch of key words you can search for. For example matrix with non-zero data gives us a number of reference pages for programming languages, the majority of which wind up referencing sparse matrices. I’ll note that there are several iterations which do not give the results you want, like matrix of zeros. Generally I find explicitly calling out what you want, rather than something adjacent will give you the best results.

Here’s the thing though. It doesn’t actually save us much time if any. Our data isn’t sparse enough, as we rapidly discovered looking at what the final soluton turns out to be. We have about as many 1’s as 0’s, and the performance gain isn’t there. Its the beginning of a solution path that will actually bear fruit, but the key word “sparse matrix”, isn’t where the solution lies.

What the final solution looks like. Thanks Dave.

The important takeaway here is that we don’t care about zeroes. In fact, we could be in an infinitely large grid, and it wouldn’t matter, since only the bounds of our instructions are relevant…

Rectangles

The matrix solutions didn’t sit right with me, because ultimately they’re an inelegant representation of coordinate sets. You know what also defines an arbitrary region of space on a grid? A rectangle. Taking the previous idea of overlapping instructions, if we represent each instruction as an area, we avoid the issue of needing to instantiate a matrix for each new instruction set.

Simple enough… except we have to do it all in one iteration to compete with the brute force solution. We can’t just generate a set of instructions as rectangles and then apply them on the grid, because we’re not saving any time. Instead we have to consider the primary grid (the one we claimed not to care about earlier.) as a rectangle on top of which we’re playing the other rectangles. This gets hairy, fast. Not that that’s going to deter us.

The goal of course, is to not need to execute extraneous instructions by eliminating unneeded rectangles, and then at the very end get the non-overlapping area of all lit rectangles. This seems overly complex, probably because it is, but there are several data structures that might help us, and I remain steadfast in the idea that there is an optimal solution here.

Ok, so the first problem you have to solve to fix this using rectangles is “how do you determine if two rectangles are overlapping”. You’d think this would be trivial. Its not. Its solved, but its annoying. You can do fancy vector stuff, but that was beyond what I wanted to investigate. Another solution is to check to see if any of the four corners of either rectangle is bounded by the area of the other. That takes 16 Boolean logic checks, is easy to mess up, and misses a core case.

Alright, fine, lets look at all the possible cases then. To help with this Dave whipped up a visualization in Mathematica. It boils down to four potential overlap cases:

One way to think about it is to look at the overlap of line segments, but again, there’s a lot of cases to consider there. I went as far as coding out a monster function to do this, when Dave proposed something much simpler. (It only took us 1200 words to get to the first line of code this time. By the time we reach day 25 I hope to have had a blog with no actual code.)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

use std::cmp;

struct Rectangle {

xmin: i64,

ymin: i64,

xmax: i64,

ymax: i64

}

fn rect_overlap(rect1: Rectangle, rect2: Rectangle) -> Option<Rectangle> {

let left_x = cmp::max(rect1.xmin, rect2.xmin);

let right_x = cmp::min(rect1.xmax, rect2.xmax);

let top_y = cmp::max(rect1.ymin, rect2.ymin);

let bottom_y = cmp::min(rect1.ymax, rect2.ymax);

if left_x <= right_x && top_y <= bottom_y {

return Some (Rectangle {

xmin: left_x,

ymin: top_y,

xmax: right_x,

ymax: bottom_y

})

} else {

return None

}

}

This is much more elegant, and doesn’t require doing the various checks I was doing in my initial iteration, while working on roughly the same principles.

Alright, now we can determine if rectangles overlap, what’s next?

Obviously we just start putting rectangles down on a grid. There’s just one issue. Every time we put a rectangle down we have to check if any existing rectangle overlaps. If it does, we have to generate new rectangles to represent the different states. We can be tricky and avoid some cases, such as where a rectangle is fully enveloped by a rectangle of the same color, but it starts to explode.

A minor issue

This is… non-ideal. Other, less determined people might have concluded their intuition was wrong, and moved on, done useful things with their lives. Not us.

Obviously we have a lot of rectangles. There’s a couple different ways to help deal with that. The first is to add naïve optimizations. Remove rectangles already inside rectangles, add logic for when to skip adding. We tried this, and discovered several fun bugs, all of which were Mathematica-specific and not really relevant to the project. What we discovered though is that to make these optimizations we had to run various comparisons on every rectangle every time a new rectangle was created. This is the opposite of optimal.

It looked pretty cool though

Clearly what we need is a data structure that works well with overlapping rectangles. Surely someone has thought about this problem before?

Indeed, they have, in all kinds of contexts. Turns out we’re not the first to deal with rectangles. We discovered a couple data structures that looked promising. To whit, KD-Trees and R-Trees.

A forest of trees

I’m not an expert on these data structures, so I’ll mostly be giving a layman’s interpretation of obtuse Wikipedia articles and a paper or two we read along the way. Ultimately, we wound up implementing neither of these, so if you don’t care about data structures feel free to skip this section.

Alright, so, what is a KD-Tree, and why do we think it applies? A KD-Tree is a binary tree, that is each node has a maximum of two children. In a KD-Tree each node is a coordinate pair, or in some special cases, a set of coordinate pairs. A KD-Tree specifically organizes coordinate sets so you split space into sub-regions, theoretically letting you get specific pairs in log(n) time. The Wikipedia page explicitly calls out that Instead of points, a k-d tree can also contain rectangles or hyperrectangles. Obviously if we could run a search that only got us the rectangles we cared about that would make our overlapping areas problems significantly easier.

But there is a catch. Building the tree is a O(n * log(n)) operation. Which might still be faster than O(nm), but might not, since we have to add to the tree at every step. The tree will likely become unbalanced and require a rebuild every so often, adding complexity. This seemed unsuitable, especially as we couldn’t find a single good example of someone using a kd-tree with rectangles in a way we could parse into working code.

R-Trees on the other hand looked extremely promising, I mean, look at this image:

Glorious glorious rectangles

The idea behind r-trees, it seems to me, is you draw rectangles around your existing rectangles, and each node is an array (or linked list) of rectangles, which might contain sub-rectangles. Getting an area of all overlapping rectangles seemed pretty promising, as it could potentially mean looking at one thousand rectangles for comparisons, rather than a million. It has one tiny issue of course. R-trees do not guarantee good worst-case performance. They also are difficult to build, as the algorithms to determine where and how to bound rectangles were beyond me.

It’s extremely likely an r-tree would have worked for our use case, but its around this time I got this message from Dave:

I figured out an intermediate solution, in between the kind of solution we wanted and brute force.

Good enough?

Remember our conversation about sparse matrices, before I went down into data-structure land and talked way too much about rectangles? It turns out we were on to something.

I’m gonna throw a big block of code in here, and then talk about it. I also want to point out that other than helping refine some of the code, this was fundamentally Dave’s work, in an effort, I’m sure, to get me to stop trying to implement R-Trees.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

use std::fs;

use std::time::{Instant};

use std::collections::HashMap;

#[derive(Debug, Eq, Hash, PartialEq)]

struct Rectangle<'a> {

xmin: i64,

ymin: i64,

xmax: i64,

ymax: i64,

light: &'a str

}

fn main() {

let start = Instant::now();

let file = "../Inputs/Day6Input.txt";

let input_raw: String = fs::read_to_string(file).unwrap();

let mut rectangles: Vec<Rectangle> = Vec::new();

let mut x_range = vec![];

let mut y_range = vec![];

for line in input_raw.lines() {

let mut tokens = line.split(|c| c == ' ' || c == ',');

let mut keyword = tokens.next().unwrap();

if keyword == "turn" {

keyword = tokens.next().unwrap();

};

let xmin: i64 = tokens.next().unwrap().parse().unwrap();

let ymin: i64 = tokens.next().unwrap().parse().unwrap();

tokens.next();

let xmax: i64 = tokens.next().unwrap().parse::<i64>().unwrap() + 1; // Plus one is critical!

let ymax: i64 = tokens.next().unwrap().parse::<i64>().unwrap() + 1;

let light: &str = keyword;

x_range.push(xmin);

x_range.push(xmax);

y_range.push(ymin);

y_range.push(ymax);

rectangles.push(Rectangle{xmin,ymin,xmax,ymax,light});

}

x_range.sort();

x_range.dedup();

y_range.sort();

y_range.dedup();

let mut x_diff = Vec::with_capacity(x_range.len());

let mut x_hash = HashMap::new();

for i in 0..(x_range.len()) {

if i < x_range.len() - 1 {

x_diff.push(x_range[i+1] - x_range[i]);

} else {

x_diff.push(1);

}

x_hash.insert(x_range[i],i as usize);

};

let mut y_diff = Vec::with_capacity(y_range.len());

let mut y_hash = HashMap::new();

for i in 0..(y_range.len()) {

if i < y_range.len() - 1 {

y_diff.push(y_range[i+1] - y_range[i]);

} else {

y_diff.push(1);

}

y_hash.insert(y_range[i],i as usize);

};

let mut first_lights = vec![vec![0i64; y_range.len()]; x_range.len()];

let mut second_lights = vec![vec![0i64; y_range.len()]; x_range.len()];

for r in rectangles {

let xmin = *(x_hash.get(&r.xmin).unwrap());

let xmax = *(x_hash.get(&r.xmax).unwrap());

let ymin = *(y_hash.get(&r.ymin).unwrap());

let ymax = *(y_hash.get(&r.ymax).unwrap());

for row in &mut first_lights[xmin..xmax] {

for val in &mut row[ymin..ymax] {

*val = match r.light {

"on" => 1,

"off" => 0,

"toggle" => if *val == 1 {0} else {1},

_ => 0

}

}

}

for row in &mut second_lights[xmin..xmax] {

for val in &mut row[ymin..ymax] {

*val = match r.light {

"on" => *val + 1,

"off" => if *val <= 1 {0} else {*val - 1},

"toggle" => *val + 2,

_ => 0

}

}

}

}

let mut part1 = 0;

let mut part2 = 0;

for i in 0..x_range.len() {

for j in 0..y_range.len() {

part1 += first_lights[i][j] * x_diff[i] * y_diff[j];

part2 += second_lights[i][j] * x_diff[i] * y_diff[j];

}

}

let end = start.elapsed().as_micros();

println!("Part 1: {}",part1);

println!("Part 2: {}",part2);

println!("Time: {} μs", end);

}

1

2

3

Part 1: 569999

Part 2: 17836115

Time: 13263 μs

Essentially, without getting too far into the weeds, this is a solution that works by not caring at all about the larger enveloping grid. Since we only track specific lights, we can expand our search area as new instructions arrive. The instructions define the boundaries. Which is nice.

Each instruction is a rectangle, and we put those in an array. We take those instructions and with some optimizations apply those until we get a final, non bounded grid.

A little fancy math, and for an n*n grid with r rectangles we get a space and time complexity that looks like this.

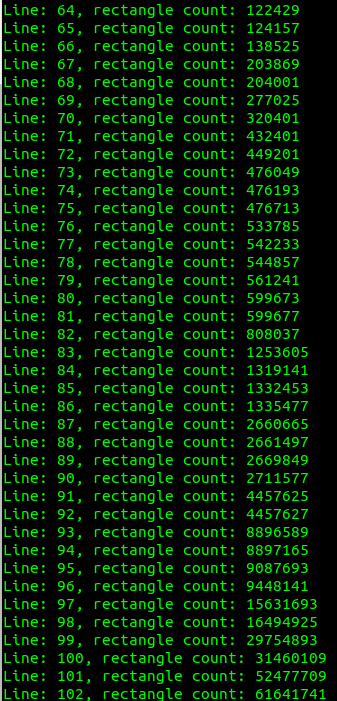

Specifically, for a given number of rectangles, this solution is far better than the brute force when the grid is large, and slightly worse than the brute force when the grid is small. It scales to a million by a million grid with no problem. However, it doesn’t scale with the number of instructions the way we would have liked. A hundred rectangles takes 1.5 milliseconds. A thousand rectangles takes 1.5 seconds. Ten thousand made my machine scream until we stopped it. It works, its a better solution, but I remain convinced its not the best solution.

Throwing the towel

At this point, we decided we’d had enough. There is probably a more clever super-optimal solution that works for a million instructions in a billion by a billion grid, but its not something we’re going to uncover today, or possibly ever. Part of solving a problem like this is knowing when to walk away and come back to it when you know more. If we were determined beyond reason to solve this, this is the point where we’d look for someone who’s an expert in the field to talk to, but we’re alright putting it to bed for now.

Of course, if you, reader, come upon a way to solve this with rectangles and r-trees, we’d be thrilled to hear from you.

This raises a question, of course. I just spent an inordinate amount of words telling you about how we failed to find the best solution. How all we did was “good enough”. About how we gave up, because the solutions we were looking at were too hard. Why? Because there’s value in failure too. I feel like every blog I read talks about some super cool success, and that’s great, its important to celebrate wins, but a lot of development is not that. A lot of writing code is bashing your head against the wall trying various angles, and having none of them work out. Googling concepts you don’t understand and realizing the descriptions are vague and doing more googling. Following your gut only to discover that it doesn’t know what its talking about. I wanted to give a glimpse of that. Show the dead ends and back alleys that you run into. Because ultimately, writing code is about a lot more than writing code. Its about failing forward.

Series

Comments powered by giscus.