This review / essay was originally posted here on Scott Alexander’s blog, Astral Codex Ten, as a finalist in the 2024 ACX Book Review Contest. I’ve had time since to proofread and fix some of the mistakes I didn’t catch the first time around, but the core of the review is the same.

I.

Suppose you were a newcomer to English literature, and having heard of this artistic device called ‘poetry’, wondered what it was all about and how English picked it up. You might start by looking up some examples of poetry from each century, going back until you can’t easily understand the language anymore, and find in the 16th century such poems as John Skelton’s “Speke, Parott” [sic]:

PAROT

My name is Parrot, a byrd of Paradyse,

By Nature devised of a wonderowus kynde,

Deyntely dyeted with dyvers dylycate spyce,

Tyl Euphrates, that flode, dryveth me into Inde;

Where men of that countrey by fortune me fynde,

And send me to greate ladyes of estate;

Then Parot must have an almon or a date.

Moving forward into the 17th century in search of poems that spell their subject matter consistently, you might come across John Donne’s “A Hymn to God the Father”:

I have a sin of fear, that when I have spun

My last thread, I shall perish on the shore;

But swear by thyself, that at my death thy Son

Shall shine as he shines now, and heretofore;

And, having done that, thou hast done;

I fear no more.

Moving forward with a bit more confidence, now that English has had a bit more time to settle on its modern form, you find in the 18th century Thomas Gray’s “Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard”:

The curfew tolls the knell of parting day,

The lowing herd wind slowly o’er the lea,

The plowman homeward plods his weary way,

And leaves the world to darkness and to me.

By now, the patterns to this ‘poetry’ thing are becoming pretty clear, but a little stale; there’s only so many one- and two-syllable rhymes available, and only so many times you can hear the word ‘yearn’ rhymed with ‘burn’ before you’re wishing for something a little more exciting. Perhaps when you reach the 19th century you’re fascinated by the new trend of comic verse with its multi-syllable rhymes, such as in The Ingoldsby Legends:

Should it even set fire to the castle and burn it, you’re

Amply insured, for both buildings and furniture…

But aside from novelties for comedic effect, you’ve started to wonder if strict rhymes are really necessary for good poetry, and perhaps you’ve started to wonder what poetry even is. So when you chance upon Walt Whitman’s “Out of the Cradle Endlessly Rocking”, you sit bolt upright. This is something new:

Out of the cradle endlessly rocking,

Out of the mocking-bird’s throat, the musical shuttle,

Out of the Ninth-month midnight,

Over the sterile sands and the fields beyond, where the child leaving his bed wander’d alone, bareheaded, barefoot,

Down from the shower’d halo,

Up from the mystic play of shadows twining and twisting as if they were alive,…

If you stop right there and decide to write a book about the trip, you’re in all likelihood Clement Wood, putting together The Complete Rhyming Dictionary and Poet’s Craft Book in 1936. You have a grand vision in front of you about poetry, with very clear ideas as to what direction it’s going to take. There’s such a large body of poetry in English that a little bit of polyrhythm in place of strict iambic metre (or even better, this new-fangled eighty-year-old invention called ‘free verse’), and consonance or assonance instead of strict rhyme, could introduce some much-needed fresh blood into the scene. You dream of a day in which poetry is “a regular pattern, with restrained freedom and variety in its use”. You forsee a time when the various fixed forms like sonnets and ballades will have been enhanced by a healthy dose of irregularity, unlike the unforgiving metre the “poets, bound by fossilized conventions” of your day would prefer. And, eventually, a decade and a half after the book, you die peacefully, having completed a wondrous journey.

Though Clement Wood himself didn’t live to see it, we could imagine him continuing his trip up to the 21st century, leafing through the proceedings of the UK National Poetry Competition, and reading the opening lines to 2019’s winning entry, Susannah Hart’s “Reading the Safeguarding and Child Protection Policy”:

has left me feeling vaguely sick and I think a walk

is probably the answer, is often said to be the answer,

though I now understand physical intervention must

not be undertaken lightly and the appropriate training

must be given because the policy is designed to prevent

the impairment of health or development even though it has had

the opposite effect on me as currently I feel impaired, uneven,

unequal to the task of being real, such that it occurs to me

that humankind seems to be trying to find ever more

ingenious ways to make the bearing of reality more difficult,

else how could anyone have thought of all the horrible

things that someone somewhere is always doing

to someone else, whose vulnerabilities may or may not

include neglect, homelessness, mental health issues,

bereavement, previous abuse, but then again humankind

has form for this kind of thing as medieval warfare…

Something weird happened to English poetry in the 20th century.

II.

The Complete Rhyming Dictionary and Poet’s Craft Book is, on the surface, a book of contradictions. It’s a rhyming dictionary, prefaced by a guide to metre and the fixed poetic forms, written by a poet sick of fixed poetic conventions in general and rhyming in particular.

In Chapter II, Clement Wood declares that “there is no need for pride if the poetry is excessively regular” and encourages “variety within uniformity”; in Chapter VI, he declares that switching an ‘and’ for a ‘but’ in the refrain of a ballade is “unforgiveable”. He spends half a page decrying poets who rhyme ‘north’ with ‘forth’, since those two do not (in an Alabama accent) make a perfect rhyme but rather a consonance; he then arranges the rhyming dictionary specifically to make consonance easier to find, since all the perfect rhymes are now overused to the point of cliché. He stresses the need to avoid archaic and obsolete words, so as to make one’s poetry timeless, and then declares that no one’s poetry can ever be timeless:

In spite of the constant insistence that nothing changes under the sun, the nature of man is stretched outward by his expanding environment, and coiled more tensely into molecules and atoms and complexes and other inner things: and the poetry, the concentrated heart’s expression, of yesterday cannot forever be the poetry of today.

These contradictions extend throughout the entire book. They’re not the fault of Clement Wood.

Two decades earlier, Ezra Pound’s essay “A Few Don’ts by an Imagiste” outlined the original guiding principles of Imagism, a literary movement aimed at making poetry more fresh, more alive, and more relevant to a public quickly getting bored of the old conventions. Reading the essay, Pound’s advice is unimpeachable, encouraging aspiring poets to raise their standards significantly, avoid plagiarism, and buckle down on learning all the nuances of language in order to produce the most striking images possible to convey with the written word:

Go in fear of abstractions. Don’t retell in mediocre verse what has already been done in good prose. Don’t think any intelligent person is going to be deceived when you try to shirk all the difficulties of the unspeakably difficult art of good prose by chopping your composition into line lengths.

…

Don’t imagine that the art of poetry is any simpler than the art of music, or that you can please the expert before you have spent at least as much effort on the art of verse as the average piano teacher spends on the art of music.

…

Let the neophyte know assonance and alliteration, rhyme immediate and delayed, simple and polyphonic, as a musician would expect to know harmony and counter-point and all the minutiae of his craft. No time is too great to give to these matters or to any one of them, even if the artist seldom have need of them.

…

Don’t be descriptive; remember that the painter can describe a landscape much better than you can, and that he has to know a deal more about it.

The classic poets reacted to these sage words of wisdom precisely the way you’d expect someone in the late 1910s to react: declaring, like John Burroughs did, that Imagism was to literature what Communism was to politics:

A class of young men who seem to look upon themselves as revolutionary poets has arisen, chiefly in Chicago; and they are putting forth the most astonishing stuff in the name of free verse that has probably ever appeared anywhere.

…

The trick of it seems to be to take flat, unimaginative prose and cut it up in lines of varying length, and often omit the capitals at the beginning of the lines—”shredded prose,” with no “kick” in it at all. These men are the “Reds” of literature. They would reverse or destroy all the recognized rules and standards upon which literature is founded. They show what Bolshevism carried out in the field of poetry, would lead to.

…

A degenerate Englishman may be brutal and coarse, but he could never be guilty of the inane or the outrageous things which the Cubists, the Imagists, the Futurists, and the other Ists among the French have turned out.

This is obviously an overreaction. How could encouraging poets to work harder, to hold themselves and their work to higher standards, and to know their craft better lead to the destruction of “all the recognized rules and standards upon which literature is founded”? Poetry was clearly in rough shape by the early 1900s, and could have used some fresh blood and some improvement of standards. Similarly, Russia was clearly in rough shape in 1917, and the proletariat really did seem to have some grievances that needed to be resolved by a government more in tune with their best interests.

A few decades later, both Russia and poetry were unrecognizable. And Clement Wood, who speaks highly of Imagism and Imagist poets throughout the entire book, ran for mayor of Burmingham in 1913 for the Socialist Party of America. So maybe Burroughs was onto something.

Clement Wood writes this book as an honest appraisal of poetry as it existed in 1936. And the consensus he accurately reproduces was that the old ways of poetry, the rhyme and strict metre and the various fixed forms (almost all of which were stolen from France, and we didn’t even steal half the French ones), had been good things, once upon a time. But now, they were good only as a way of teaching, only as a transitional stage to something better. For instance, see his introduction to Chapter VI, teaching the various fixed forms:

Fixed forms of poetry tend to become outgrown, like a child’s shirt too small to close over a man’s heart. They then become relegated to minor versifiers, to light verse writers, and to college and high school exercises.

Wood’s central thesis is that as poetry gets older and more familiar, its various forms and patterns become less and less suitable for serious expression, and so naturally become relegated to either children (as a stepping-stone to the adult world of poetry) or to comedy. We’re grown-ups now, and we can’t take classic poetry seriously anymore:

Poetry itself ages: Shakespeare, Milton, Virgil, and Horace, are more used in the classroom than in the living room today, and so of the rest of them.

If this is true of the poetry itself, it is truer of the patterns in which poetry has been uttered, and especially of the fixed forms. The sonnet, an emigrant from Italy that became naturalized in English literature, still holds its own as a major method of expressing serious poetry, in the eyes of many poets and readers. Even at that, it is now regarded as puerile by the extreme advocates of free verse or polyrhythmic poetry, especially since Whitman and the Imagist movement. Numerous other alien verse forms did not fare so well, and have established themselves primarily as mediums for light and humorous verse. These include the ballade, the rondeau, the villanelle, the triolet, and so on. This may be because of their rigid rules and formal repetitions, which were not acceptable to the living poet. And yet, they started as seriously as Sapphics, heroic blank verse, or polyrhythms…

Compare this to his conclusion about free verse, in the previous chapter:

The free verse writer devises his own line-division pattern. This form, eliminating the devices of metre and rhyme, calls on the poet to avoid the inconsequential and the trivial, and to write down only his important utterances. If rhyme is a shelter for mediocrity, as Shelley wrote in his preface to The Revolt of Islam, free verse is a test of the best that the poet has in him.

In this light, the contradictions throughout the whole book make sense. There are two types of verse worth writing: actual poetry, mostly consisting of free verse, and training poetry. Rigidity isn’t suitable for actual poetry, argues Wood, since every beautiful sonnet has already been written, and all the possible 3,848 good Spenserian stanzas were used up by Spenser, and all the good ballades are in French. Come up with something new, when you have something new to say.

But when training, rigidity is the entire point! You wouldn’t be surprised if a basketball coach yelled at a player who threw a perfect three-point shot, if it was done during a drill for passing. Three-point shots are fine, but they’re not the goal right now, and if you only focus on doing them you won’t learn how to pass. And so rhyming ‘north’ with ‘forth’ (in an Alabama accent) becomes worthy of half a page of angry correction, even if real poetry – the kind the cool Imagists write – doesn’t rhyme at all. Rhyming teaches you how words and phrases fit together, and reference each other. Metre teaches you how words and phrases flow, and how to transition from one to the next. Both force you to constrain your own writing, to think of a dozen ways to say the same thing until you find the perfect fit. All they’re good for is training – but you can’t become a poet without training.

III.

The obvious follow-up question: is the book good for training? Simple answer: yes. And if – don’t say this too loud, lest Clement Wood hear you – if you don’t want to ‘graduate’ to free verse afterwards, but only want to want stay in school and write sonnets, the book will get you a large portion of the way there.

The primary strength of the book, as a guide to writing poetry as opposed to a snapshot of history, is in its own poem selections. Clement Wood quotes 103 different poems by 63 different authors (plus anonymous ones), of every conceivable style and (importantly) of a broad range of quality. And given that everything is available online, it’s selection and not content that makes a physical book worthwhile. Wikipedia could tell you the difference between masculine, feminine, and triple rhymes (rhyming pairs of words ending in zero, one, or two unstressed syllables, respectively). But Wood finds the perfect poem to demonstrate all three at once, to show the contrast, with Guy Wetmore Carryl’s “How the Helpmate of Blue-Beard Made Free With A Door”:

A maiden from the Bosphorus

With eyes as bright as Phosphorus

Once wed the wealthy bailiff

Of the caliph

Of Kelat.Though diligent and zealous, he

Became a slave to jealousy.

(Considering her beauty,

‘Twas his duty

To be that!)

Similarly, Wood and Wikipedia alike use Longfellow’s “Hiawatha” to demonstrate trochaic tetrameter (poems with eight-syllable lines, with a stress pattern going TUM ta TUM ta TUM ta TUM ta). But Wood goes the extra mile and invents several variations of the same stanza from “Hiawatha” to make it iambic trimeter, and trochaic tetrameter, and trochaic trimeter, to reassure the reader that switching between the metres isn’t too challenging. Wikipedia gives good examples of each type of rhyme and metre. Wood shows why the good examples are good, and also why the bad examples are bad, invariably getting the latter from Robert Browning. In an age where everything is available online instantly, it’s the curation that’s difficult to get elsewhere.

The second half of the book, the actual rhyming dictionary, is useful for a different reason. Rhymezone has every word in this rhyming dictionary and then some, including words that hadn’t yet been coined in 1936, and it’s much faster to type a word into Rhymezone than to look it up phonetically and by unstressed syllable count in the 494-page dictionary in the back. If the point is to write a poem, then Rhymezone is far better. But if the point is training, to get better at writing poetry, then taking fifteen more seconds to look up a rhyme is fifteen more seconds to think of the rhyme yourself, and get to the point where you don’t need a rhyming dictionary.

Because that is ultimately the goal Clement Wood is trying to help an aspiring poet reach with this book: to not need a rhyming dictionary anymore. Granted, he wants you not to need it because you aren’t rhyming anymore. You might want to not need it for a different reason. But your interests still align.

IV.

Why the 1936 edition?

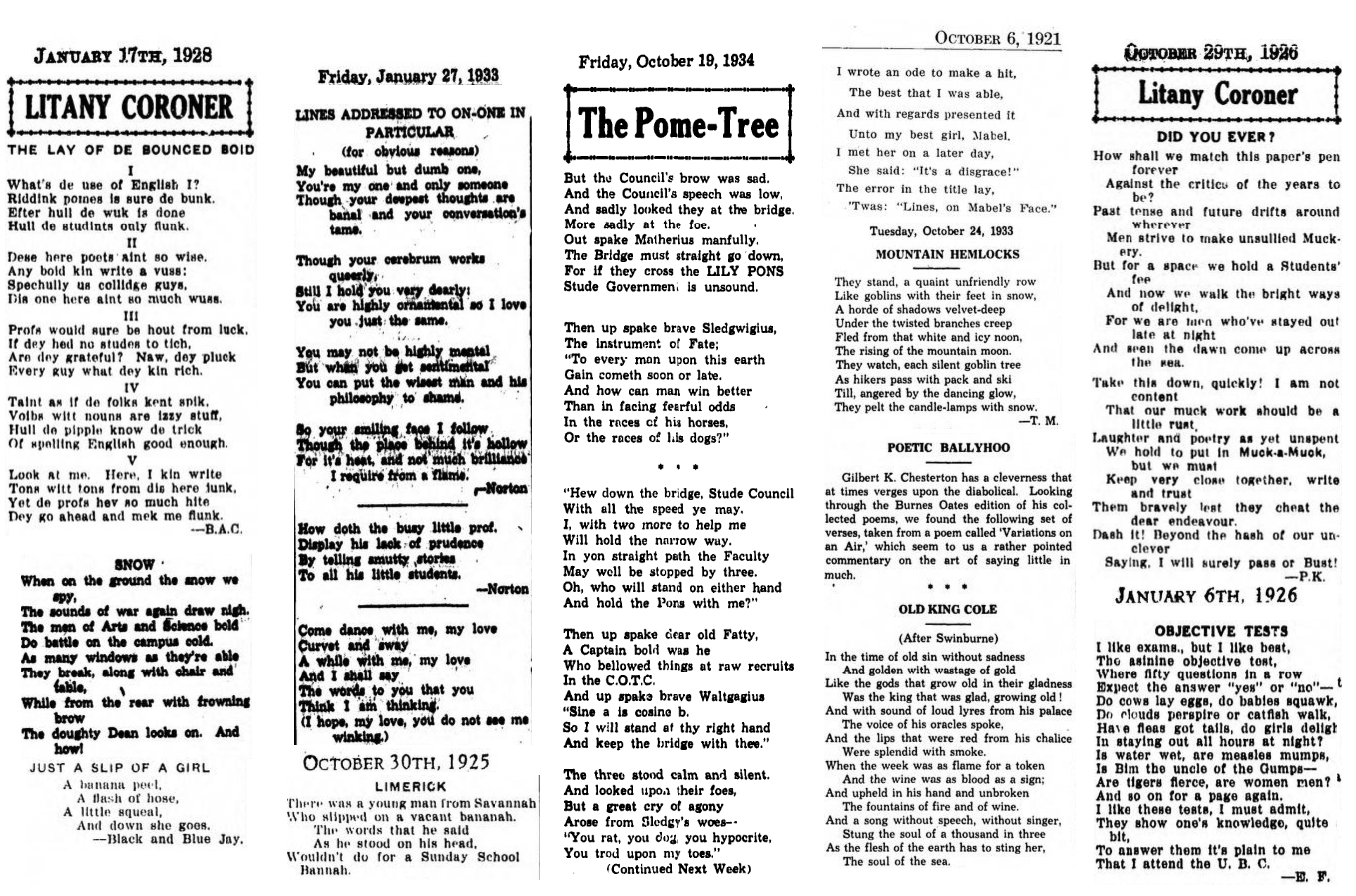

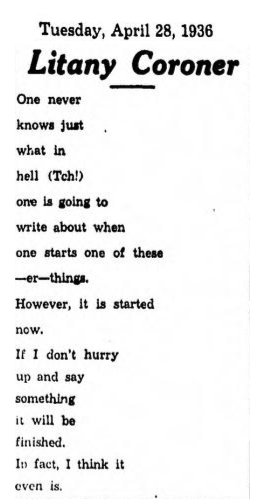

Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, the student newspaper of the University of British Columbia (affectionately named the ‘Ubyssey’) would run various comic poems and light verse in a recurring feature, alternately titled “Litany Coroner”, a variation on “POME”, or in one case, “Poetic Ballyhoo” (featuring GK Chesterton, who probably would have approved of being there). These poems were, mostly, submitted by students, and can’t be found anywhere else online. They were, mostly, written with traditional rhyme and metre, with some free verse here and there. They were, mostly, not the highest-caliber poems you’ll ever read.

1936, however, was a bad year for poetry. Rudyard Kipling died, having at one point been the most widely-read contemporary poet in the English language. G.K. Chesterton died, still remembered today by the online limerick dictionary in limerick form (“Let us celebrate Gilbert Keith Chesterton / All who heard him were deeply impressed at an / Amply earnest debate / Where his words carried weight / And his own weight was, one would have guessed, a ton.”). Harry Graham died, who I had never heard of, but who Clement Wood quotes more than any other 20th century poet, exclusively in poems featuring macabre humor about dead babies (don’t ask me).

And, in one of the final poems of the now-appropriately-named “Litany Coroner”, the Ubyssey inadvertently buried them:

The 1936 edition was made right in this transitional time between ‘classic’ and ‘modern’ poetry, and in many ways represents the best of both. Poetry, in academia and among the kind of people who write rhyming dictionaries, was stale in the early 20th century. Sure, Kipling and Chesterton and Graham were all writing bestsellers, but they didn’t show up in academia itself - the closest they got were the student newspapers. And while they could all write in any fixed form or rhyme scheme or metre, they tended to favor simpler ones, not the rondeau or the villanelle or the triolet that academics a few decades earlier might have preferred. Wood warns, both in the introduction and again and again throughout the book, about the failure modes he sees in poets too entrenched in archaic language and wording:

The weakness of much verse and some poetry of the past is partly traceable to unoriginal teachers of English or versification, who advised their pupils to saturate themselves in this or that poet, and then write. Keats, saturated in Spencer, took a long time to overcome this echoey quality, and emerge into the glorious highland of his Hyperion. Many lesser souls never emerge. It is valuable to know the poetry of the past, and love it. But the critical brain should carefully root out every echo, every imitation – unless some alteration in phrasing or meaning makes the altered phrase your own creation.

Wood grew up in an era where the mistakes of the classical poets were still in living memory…and so were their successes. He can devote as many pages to “Little Willies” as he does to limericks, even though “Little Willies” are unheard of today, because they were a popular fad, because 1936 was at the tail end of the era where poetry could still have popular fads, as opposed to academic schools and fashions. He can care about both tragic and comic verse equally, and care as much about appealing to a contemporary audience as appealing to an imagined future readership.

Appealing about contemporary audiences is also, ironically, the book’s strongest recommendation from the perspective of a reader 88 years in the future. Consonance (matching consonant sounds but differing vowel sounds) was just getting big, and Wood is convinced that assonance (the opposite, matching vowel sounds with different consonant sounds) was going to join it on the big stage any day now. He’s equally convinced that contemporary audiences want variation within metre: the formal metre (e.g. iambic pentameter, da DUM da DUM da DUM da DUM da DUM) is the skeleton of the verse, but people need a lot more than just a skeleton to qualify as ‘alive’. Listening to most random songs in most genres, he’s more right now than he was in 1936; assonance and consonance are at least as common as true rhymes, and the musical instrument can set a strong enough rhythm that the actual verses can be longer or shorter by several syllables. Modern music – or the good portion of it – requires the kind of flexibility that Wood tries to teach, even if modern poetry is as formless as water and modern classic-style poetry as rigid as rock.

On the flip side, Wood can write about free verse from the perspective of a poet who grew up with, and at one time genuinely loved, the fixed forms. My sole opinion on free verse came from a pithy G.K. Chesterton quote (“Free verse? You may as well call sleeping in a ditch ‘free architecture’.”), but reading this book showed me how and why someone might hypothetically like it, and what someone might hypothetically get out of reading it. He didn’t convince me to like it. But I can’t quite sneer like I used to.

If you are interested in poetry but absolutely despite free verse, however, the book still provides a glimmer of hope: Clement Wood argues quite persuasively that no form of poetry can last forever, including whichever form you personally can’t stand. Robert Frost, in his lesser-known 1936 poem “Tendencies Cancel”, agreed with and wrote about wood:

Will the blight kill the chestnut?

The farmers rather guess not.

It keeps smouldering at the roots

And sending up new shoots,

Till another parasite

Shall come to kill the blight.

Overall, to anyone who wants a genuine introduction and reference guide to the art of poetry, I highly recommend the 1936 edition of The Complete Rhyming Dictionary and Poet’s Craft Book.