The Radical Idea

Scott Alexander, at Astral Codex Ten, recently posted an interesting list of crazy ideas he wishes someone would try. The fourth crazy idea in particular caught my attention: it was a crazy idea about language learning.

[I]magine this - I’m going to use Japanese here because it’s the only language I could even remotely try to use as an example without making a total fool of myself, and I’ll thank you for not correcting the inevitable errors. The course is a novel. Could be any novel, but I imagine for cutesiness reasons you’d want to use a classic from the culture you’re studying, like The Tale of Genji or Death Note.

The first chapter is just the first chapter of the novel in English. It would contain normal English sentences like “Ryuk taught Light the secrets of the Death Note.”

The second chapter is still in English, but it’s a weird English with a sentence structure a bit more reminiscent of the foreign language. It might change to something like “Ryuk the secrets of the Death Note to Light taught”. (I’m keeping the sentence the same to make it obvious what’s going on here, but of course in the real book it would be the second chapter, not just a repetition of the first).

The next chapter would do the same thing, but get a little more foreign, maybe “About Ryuk, secret of Death Note to Light taught”

And gradually it would get a little more so: “Ryuk-about, Death Note-of secret Light-to taught.”

There would be enough of this that sentences with Japanese syntax would become as quickly and effortlessly readable as sentences with English syntax. And the hope is that the reader would keep going because they’d be enjoying the story, and after a little while adjusting the weird sentence structure would be a comparatively slight barrier to further progress.

Then some of the grammatical particles would switch to full on foreign. Now it’s “Ryuk-wa, Death Note-no secret Light-e taught.” Gradually we’d get through all of the horrible little verb bits where my language studies have previously crashed and burned: “Ryuk-wa, Death Note-no secret-o Light-e teach-mashita.”

I might grudgingly allow little footnotes at the bottom like “This is the first time you’ve seen -mashita. It’s just the standard past tense ending for verbs”, but even that might be an unacceptable surrender to the grammar-memorization-industrial complex.

Finally, and very gradually, it would start replacing English words with Japanese words. Just simple ones at first, ones that were obvious from context, and of course there would be a glossary in the back of the book you could look them up in if you had trouble.

Finally, the last chapter would just be completely in Japanese: “Ryuk wa Desu Noto no himitsu o Light e oshiemashita.” It would probably be very deliberately simplified Japanese, but still, if you can read a book chapter in Japanese that seems like a pretty good success condition for an Intro Japanese textbook.

([A]nd of course Japanese is a bad example here because you’d have to learn the writing system separately. I’d have preferred the example in Spanish, but I’m not confident enough in my Spanish even to do a simple example sentence.)

On the face of it, this idea doesn’t sound unreasonable. So let’s try it.

Ovid’s Metamorphoses

I picked Latin for the same reason Mr. Alexander picked Japanese, and I picked Ovid’s Metamorphoses because it seemed fitting on every level. It’s a foundational work, it doesn’t lose that much by being translated into prose instead of poetry (unlike the Aeneid), has relatively simple verbage (unlike e.g. Cireco, or St. Paul’s epistles in the Vulgate), and I couldn’t think of a work with a more suitable title or theme.

I took the first handful of lines from each of the fifteen books in the epic, and provided them, along with the original Latin and with a mostly literal (and correspondingly mostly bland) English translation.

Book I

Latin: In nova fert animus mutatas dicere formas corpora; di, coeptis (nam vos mutastis et illas) adspirate meis primaque ab origine mundi ad mea perpetuum deducite tempora carmen!

English: I wish to speak of bodies changed into new forms. You gods (since you are the ones who alter them), inspire my song, and spin out a continuous thread of words from the beginning of the world to my own times!

Book II

Latin: Regia Solis erat sublimibus alta columnis, clara micante auro flammasque imitante pyropo, cuius ebur nitidum fastigia summa tegebat, argenti bifores radiabant lumine valvae.

Subject-Object-Verb Word Order: The Palace of the Sun was lofty on tall columns, bright with gleaming gold and aflame as if to mimic rubies, whose polished ivory the very summit covered. Silver light radiated from the double doors.

Book III

Latin: Iamque deus posita fallacis imagine tauri se confessus erat Dictaeaque rura tenebat, cum pater ignarus Cadmo perquirere raptam imperat et poenam, si non invenerit, addit exilium, facto pius et scleratus eodem.

Purely Literal Word Order: And now the god, having cast off the false image of a bull, had confessed himself, and Crete’s lands held. With the father unknowing, Cadmus to search everywhere for the kidnapped he commanded, and to the punishment, if he did not find, he added exile, making himself pious and cursed by the same action.

English: And now the god, having cast off the false image of a bull, had revealed himself, and held Crete’s lands. [Europa’s] father, not knowing this, ordered Cadmus to search everywhere for the kidnapped [girl], and decreed exile to be the punishment of failure; he thus made himself pious and impious by the same action.

Book IV

Latin: At non Alcithoe Minyeias orgia censet accipienda dei, sed adhuc temeraria Bacchum progenium negat esse Iovis sociasque sorores inpietatis habet. Festum celebrare sacerdos inmunesque operum famulas dominasque suorum pectora pelle tegi, crinales solvere vittas, serta coma, manibus frondentis sumere thyrsos iusserat et saevam laesi fore numinis eram vaticinatus erat.

Verb-endings: But not Alcithoe, of Minyeias, of the secret rites approve-does, in acceptance of the god. But thus far, recklessly Bacchus offspring denies to be of Jupiter’s, and companions sisters in impiety hold-does. The feast celebrate-to the priest released from work the female servants and their ladies, breasts with pelts cover-to-be, from hair ribbons untie-to-be and garlands en-circle-to, in the hands fronds take-to thyrisi order-did, and fierce offend-had-been to-be of the god anger prophesy-had.

English: But Alcithoe, the Minyeisian, does not approve of the rite to honor the god. She still rashly denies that Bacchus is the son of Jupiter, and she counts her sisters as companions in her inpiety. To celebrate the feast, the priest had ordered the handmaids released from work, the ladies to cover their breasts with pelts, to untie their ribbons and encircle their hair in garlands, and to take thyrisi fronds in their hands, for he had predicted that the offended god’s wrath would be fierce.

Book V

Latin: Dumque ea Cephenum medio Danaeius heros agmine commemorat, fremida regalia turba atria conplentur, nec conjugialia festa qui canat est clamor, sed qui fera nuntiet arma; inque repentinos conviva versa tumultus adsimilare freto possis, quod saeva quietum ventorum rabies motis exasperat undis.

Noun-endings: While-and Cepheus-to middle-of Danae-born-of hero procession-amid [these things] recount-does, loud uproar-with the royal hall filled-is. Neither wedding-feast-about he who sings is the noise, but he who savage threaten-does weapon-s. You the sudden tumult-s party turn-did liken-to sea-to could, which savage quiet winds-of madness move-ing irritate-does waves.

English: And while the hero, born of Danae, recounts these things to Cepheus amidst the procession, the halls of the palace are filled with a loud uproar. Not like he who sings an epithalamium is the noise, but like he who threatens with savage weapons. You could liken the sudden tumult of the party to a peaceful sea, whipped into a tempest by the violent rage of the winds.

Book VI

Latin: Praebuerat dictis Tritonia talibus aures carminaque Aonidum justamque probaverat iram; tum secum: ‘laudare parum est, laudemur et ipsae numina nec sperni sine poena nostra sinamus’.

Noun-endings (Latin): Provide-did word-is Aethena excellent-ibus [her] ear-es, and song-a Aonian righteous-am approve-did anger-am; then herself-to: “praise-to little-um is, praised-let-us-be, and ourselves-ae divinity-a not spurn-to-be without punishment-a our-a allow-we.”

English: Tritonian [Minerva] had listened to every word, and approved of the righteous anger of the Aonian’s song, then to herself thought: “It is not enough to give praise, we must also be praised ourselves - we should not allow our power to be scorned without punishment.”

Book VII

Latin: Iamque fretum Minyae Pagasea puppe secabant, perpetuaque trahens inopem sub nocte senectam Phineus visus erat, juvenesque Aquilone create virgineas volucres miseri senis ore fugarant, multaque perpessi claro sub Jasone tandem contigerant rapidas limosi Phasidos undas.

Verb-endings (Latin): And now strait-um Argonaut-ae Pagasean-a ship-e cut-through-abant, and forever-a drag-ens helpless-em under night-e ancient-am Phineus seen-erat, bird-like-as Harpy-as miserable-i old-man-is mouth-e drive-erant. And many-a [trials-a] endured-i bright-o under Jason-e, at last reach-erant rapid-as muddy-i Phasis-os wave-as.

English: And now the Minyans (Argonauts) were cutting through the sea on their Pagasean ship. They appeared to Phineus, still dragging out his old age in perpetual blindness, and the winged sons of the North Wind [Calais and Zetes] had driven the bird-like Harpies away from the miserable old man’s presence.

Book VIII

Latin: Iam nitidum retegente diem noctisque fugante tempora Lucifero cadit Eurus, et umida surgunt nubila: dant placidi cursum redeuntibus Austri Aecidis Cephaloque; quibus feliciter acti ante exspectatum portus tenuere petitos.

Prepositions: Iam shine-um reveal-ente day, night-is-que chase-ante time-a Lucifer fall-it East-Wind-us, et wet-a rise-unt cloud-a. Give-ant calm-i speed-um return-untibus South-Wind-i Aeacus-is Caphalus-o-que; who-ibus happily act-i ante awaited-um harbor-us seek-ebant.

English: And now Lucifer dispels night and unveils shining day; the East Wind drops, and rain clouds gather. The gentle South Wind Wind speeds the returning passage of the ship of Aecides and Cephalus; by its serendipity, it brings them more quickly than the expected to the port they had tried to reach.

Book IX

Latin: Quae gemitus truncaeque deo Neptunius heros causa rogat frontis; cui sic Calydonius amnis coepit inornatos redimitus harundine crines: “Triste petis munus. Quis enim sua proelia victus commemorare velit?”

Pronouns, adverbs: Quae groan-us furrowed-ae-que god-o Neptune-ius hero-os cause-a ask-at forehead-is. Cui sic Calydonian-ius river-god-is begin-it: “Sad-e request-is duty-us. Quis enim sua battle-a beaten-us remember-are wish-it?”

English: Theseus, the hero and son of Neptune, asked [Achelous] why he groaned, and why his brow was furrowed. To this, the Calydonian river-god began: “You ask a sad duty. Who wants to remember the battles he has lost?”

Book X

Latin: Inde per inmensum croceo velatus amictu aethera digreditur Ciconumque Hymenaeus ad oras tendit et Orphea nequiquam voce vocatur. Adfuit ille quidem, sed nec sollemnia verba nec laetos vultus nec felix attulit omen.

Gradual Vocabulary Replacement: Inde per inmensum golden-o covered-us cloak-u sky-a leave-itur, Ciconian-um-que Hymen-us ad shore-as rush-it et Orpheus nequiquam voce call-atur. Adfuit ille quidem, sed nec solemn-ia word-a nec joyful-os face-us nec happy bring-it omen.

English: In his golden saffron robe, Hymen flew through the vast skies to the Circonian coast to answer Orpheus’ call, but in vain. Hymen had indeed been there, but neither solemn words nor a joyful expression nor a good omen brought with him.

Book XI

Latin: Carmine dum tali silvas animosque ferarum Threcius vates et saxa sequentia ducit, ecce nurus Ciconum tectae lymphata ferinis pectora velleribus tumuli de vertice cernunt Orphea percussis sociantem carmina nervis.

Gradual Vocabulary Replacement: Carmine dum tali forest-as spirit-os-que ferarum Thracian-us poet-es et stone-a sequence-ia lead-it, behold! Daughters-in-law Cicones-um, hidden-ae skins-a wild-beast-a breast-a covered-ibus hilltop-i de vertice watch-unt Orpheus match-antem carmina struck-is string-is.

English: As the Thracian poet, with his songs, leads along the trees, and the souls of wild beats, and the procession of stones behind him, behold! See how the frenzied daughters-in-law of Cicones, breasts covered with animal skins, watch Orpheus from the hilltop as he matches his songs with plucked strings.

Book XII

Latin: Nescius adsumptis Priamus pater Aesacon alis vivere lugebat: tumulo quoque nomen habenti inferias dederat cum fratribus Hector inanes; defuit officia Paridis praesentia tristi, postmodo qui rapta longum cum conjuge bellum attulit in patrium.

Gradual Vocabulary Replacement: Nescius adsumptis Priamus pater Aescacon wing-is live-ere mourn-ebat: tomb-o quoque nomen habenti offerings-as give-erat cum fratribus Hector empty-es; lacking-it duty-ia Paris presence-ia sad-i, postmodo qui kidnapped-a lengthy-um cum wife-e bellum bring-it in patriam.

English: The father Priam mourned for his son Aesacus, not knowing that in his winged form he lived on. Even Hector had offered funeral rites at an empty tomb bearing his name; Paris was absent from these sad duties, since he was bringing a lengthy war to his country after his wife had been kidnapped.

Book XIII

Latin: Consedere duces et vulgi stante corona surgit ad hos clipei dominus septemplicis Ajax, utque erat inpatients irae. Sigeia torvo litora respexit classemque in litore vultu intendensque manus ‘agimus, pro Jupiter!” inquit.

Gradual Vocabulary Relpacement: Sit-down-ere duces et vulgi stand-e coron-a surgit ad hos shield-i dominus seven-fold-icis Ajax, utque erat inpatients irae. Sigeian-a pitiless-o shore-a respexit fleet-que in shore-a vultu, stretch-ens-que manus: “Agimus, pro Jupiter!” inquit.

English: The captains sat and the men stood in a circle around them when Ajax, lord of the seven-fold shield, leapt up, impatient with anger. With a pitiless gaze he beheld the Sigeian shore and the fleet on the shore, and reaching out his hands, cried “By Jupiter, we march!”.

Boox XIV

Latin: Iamque Giganteis iniectam faucibus Aetnen arvaque Cyclopum, quid rastra, quid usus aratri, nescia nec quicquam iunctis debentia bubus liquerat Euboicus tumidarum cultor aquarum, liquerat et Zanclen adversaque moenia Regi navifragumque fretum.

Gradual Vocabulary Replacement: Iamque Giganteis iniectam jaw-ibus Aetnen arvaque Cyclopum, quid rastra, quid usus plow-i, nescia nec quicquam iunctis debentia bull-ubus liquerat Euboicus swelling-arum cultor aquarum, liquerat et Zanclen adversaque wall-ia Regi shipwrecking-que fretum.

English: And now [Glaucus], the fisher of the swelling waters of Euboicus, escaped from the jaws of the Aetnen giants, and from the land of the Cylopes, who do not know the plow and owe nothing to the yoked oxen. He also abandoned Zancle, across from the walls of Rhegium, and the dangerous shipwrecking strait between them.

Book XV

Latin: Quaeritur interea qui tantae pondera molis sustineat tantoque queat succedere regi: destinat imperio clarum praenuntia veri Fama Numam; non ille satis cognosse Sabinae gentis habet ritus, animo maiora capaci concipit et, quae sit rerum natura, requirit.

English: Meanwhile [the Romans] wondered who could bear such a tremendous weight and succeed such a great king: Fame, the clear-seeing true harbringer, destined Numa [for the throne]. Not satisfied with knowing the rites of the Sabine people, his spirit was capable of greater, and he sought [to know] the true nature of things.

Post-mortem

Reading these passages again, it’s fairly obvious that this specific attempt does not work. From Book IV and onward, I find it harder even after writing it myself to read the partial translation than to read the Latin; I can’t imagine it’s more intuitive to one reading for the first time. But this attempt was an afternoon’s effort, without real thought put into the linguistic progression used; it’s a useful lower bound, but doesn’t answer the original question Mr. Alexander asked. Not does it work, but could it work?

For several reasons, I now think ‘no’.

To Restless Action Spurs Our Fate

Latin has an extremely fluid word order; while the normal structure is subject-object-verb, and while normally modifiers are close to the words they modify, neither of these is a hard-and-fast rule, and both have numerous exceptions in just the excerpts shown above. Worse, the order is not arbitrary. In the same way that “I never said she took my money” has a different meaning for each of the seven words you could choose to emphasize, Latin’s word order acts to provide emphasis and another layer of meaning atop the literal connotations of the words. And the only way Latin can get away with it - the only way - is that its declension system make it clear which words refer to which others.

To pick a relatively simple sentence out of the middle of Book IX:

- Latin: Quid si tibi mira sororis fata meae referam?

- English: What if I told you about the wondrous fate of my sister?

- Literal word-order translation: What if to you wondrous sister’s fate my I told?

We know from the declensions that mira can only be referring to fata, that meae can only be referring to sororis, and we know in a way that’s very hard to convey in English that upon first hearing mira and fata, before getting to the verb which tells us precisely what variation of tell we’ll experience, we know that we’re going to be told about a wondrous fate, instead of being given a wondrous fate, and instead of being shown something that happened by means of a wondrous fate. And we know immediately upon getting to mira, that it’s not the sister that’s wondrous, that there must be some other wondrous thing that we’re going to be told. Every sentence is like this.

The word order is not arbitrary. There are patterns. It can be learned, and it can make sense. But it doesn’t make sense in English, at all, and to the degree that you’re thinking in terms of English sentences and English word orders, it won’t flow, and you won’t be able to learn those difficult-to-quantify patterns. At best, you’ll be scanning each sentence back and forth, thinking “Okay, there’s mira, it’s an adjective, let’s look for a first-declension nominative / accusative / ablative noun or maybe a second-person neuter plural nominative / accusative, ahh, here’s fata, okay, let’s go back to sororis, makes sense, here’s fata again, still waiting for the verb, let’s go to meae, must fit sororis, ahh, here we have the verb at last, …”. And while that sort of thought process is good to fall back to, to parse a garden-path sentence now and again, it’s no way to learn and understand a language. That kind of thinking is what makes it possible to learn a language, yet for the language to still be dead.

And this brings us to the next problem.

When He Saw the Power of Troy Decline

There are five declensions (one of which has many small variations, and all of which have some exceptions) and four conjugations (plus the irregular verbs). In the previous sentence, fata was a first-declension noun which had in mira a first-declension adjective. The connection between them isn’t hard to make, even if all you know is “look at the final letter”. But when dealing with sororis, third-declension noun, and meae first-declension adjective, the connection is much less obvious.

It’s all well and good to read “and song-a Aonian righteous-am approve-did anger-am” and figure out that the anger is righteous, but when the description of the men serving under bright Jason is “claro sub Jasone”, it’s not clear at all that Jason is bright, or indeed (since there’s a preposition in between) that the two words claro and Jasone have anything to do with each other. When we see the same consistent word being used the same consistent way (we see claro...vitro to mean bright glass, and claro Pandione to describe somebody else as bright with an -e ending), it’s easier - or at least possible - to pick up the difference. But when the words are in English, there’s no rhyme or reason whatsoever to why some nouns will have first-declension endings and why some will have second, or third.

And the endings aren’t unique; when you see -am, is it because I will do something in the future with a first-conjugation verb, or because I wish I were doing something in the present with a second-conjugation verb, or because a feminine singular noun is experiencing an action? Without consistent words to attach these consistent endings to, readers will be merely guessing at similar sets of letters and hoping for the best.

Metamorph and Megamorph

This idea seemed promising at the outset, so there must be some element of it that has promise; Mr. Alexander must have hit on some truth about language, or else the idea would have seemed obviously doomed from the start. And I think that element of truth was an accidental feature of his example: the fact that he gave the same sentence over and over again, with small variations each time, each time knowing what to look for. To take the example sentence that started off this whole project:

- Ryuk taught Light the secret of the Death Note.

- Ryuk to Light the secret of the Death Note taught.

- Ryuk Light-to secret Death-Note-of taught.

- Ryuk Light-i secret-um Death-Note-ae taught.

- Ryuk Light-i secret-um Death-Note-ae teach-ebat.

- Ryuk Luci secret-um Death-notae docebat.

- Ryuk Luci arcanum Deathnotae docebat.

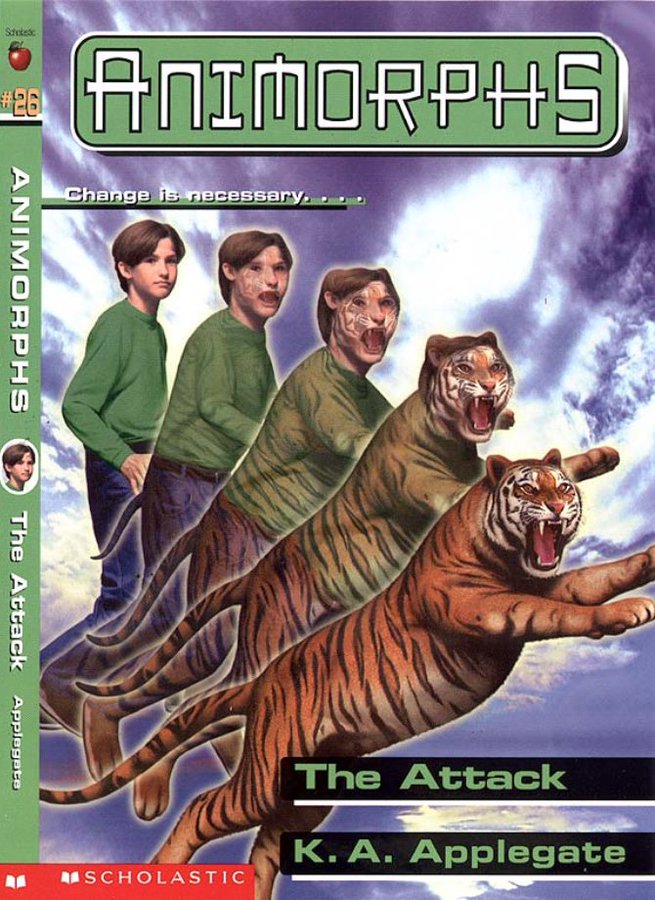

Reading down the list, the sequence of sentences is a bit like the iconic Animorphs covers, from back in the 90s. When it’s the same sentence, repeated over and over again with small variations, picking up each variation individually and keeping track of them isn’t so bad. It helps that the sentence structure is simple, that there aren’t too many confounding mixes of declensions between nouns and adjectives (or indeed, any adjectives), and that the underlying concept that the sentence is trying to convey is perfectly understandable. There’s some benefit to doing this.

But obviously, taking an existing classic text and not only making each sentence simple and understandable but also grammatically simple, carefully controlling the introduction of tense and mood and declension one piece at a time, would be difficult in the extreme. It could perhaps be done, but it would be easier to write another book from scratch.

From Scratch

Lingua Latina Per Se Illustrata, by Hans Ørberg, is that other book. Without the limitations of taking an already existing text, it can do a much slower and more gradual introduction to the grammatical concepts than I could, and does so without a word of English or any other non-Latin language, and with the text presented well before the grammar, and obvious in context. Compare my attempt at the fifteen books of Ovid’s Metamorphoses to the grammar introduced in first fifteen chapters:

- Chapter I: Singular and plural; nominative case – 1st and 2nd declensions.

- Chapter II: Masculine, feminine, and neuter; genitive case – 1st and 2nd declensions.

- Chapter III: Nominative and accusative cases – 1st and 2nd declensions. 3rd-person singular – 1st, 2nd, 3rd conjugations.

- Chapter IV: Vocative case – 1st and 2nd declensions. Imperative and indicative moods – 1st, 2nd, 3rd conjugations.

- Chapter V: Accusative and ablative cases – 1st and 2nd declensions. Plural imperative and indicative moods – 1st, 2nd, 3rd conjugations.

- Chapter VI: Prepositions. 3rd-person plural, active and passive voices – 1st, 2nd, 3rd conjugation verbs.

- Chapter VII: Dative case – 1st and 2nd declensions.

- Chapter VIII: Personal pronouns (who, whom, his, that), and pronoun ‘here’. Overview of 1st and 2nd declensions.

- Chapter IX: 3rd declension (‘pastor’ and ‘ovis’ variations).

- Chapter X: Active and passive voices, imperative mood – 1st, 2nd, 3rd conjugations. 3rd declension (‘leo’ and ‘vox’ variations).

- Chapter XI: 3rd declension (‘corpus’ and ‘mare’ variations). Accusative case with the infinitive mood.

- Chapter XII: 4th declension nouns. 1st, 2nd, 3rd declension adjectives. Comparative adjectives.

- Chapter XIII: 5th declension and undeclinable nouns. Superlative adjectives.

- Chapter XIV: Verb participles are 3rd declension nouns.

- Chapter XV: 1st, 2nd, 3rd person singular and plural verbs.

It’s a much finer degree of control than could ever be possible with a story not tailor-made for it, and gradually, piece by piece, it tells a good story. With no knowledge of Latin, the first few chapters would with illustrations probably still make sense.

Chapter I: Roma in Italia est. Italia in Europa est. Graecia in Europa est. Italia et Graecia in Europa sunt. Hispania quoque in Europa est. Hispania et Italia et Graecia in Europa sunt…

I don’t think using the English words is the correct approach, but I do think that comprehension can be gradually built up from nothing, and I do think that a consistent story, something worth reading and worth getting invested in, is the way to do it.

Iamque Opus Non Exegi

And you know what?

All of that having been written, all of that having been said, I have never before read Metamorphoses. Little sentences occasionally, in books or from quotations, but I’ve never sat down to read the whole thing. And one afternoon of looking at just the opening paragraph of each chapter has me hooked. I want to know what happened when the wild daughters of Cicones spied Orpheus plucking his lyre, and why the Calydonian river spirit was so beaten up, and why in the world Primus’ son Aescacon turned into a bird in the first place. And translating each sentence in multiple ways made me appreciate all the little turns of phrase. “Not like he who sings a wedding song, but like he who shouts a cry of arms” is weird in English but it works in Latin. I want to read the whole book now, and this post is the reason why.

To Scott Alexander: would your crazy idea help people learn languages? Yes. It’s helped me.