Part I: Art, Gone to Decay

Through thy battlements, Newstead, the hollow winds whistle:

Thou, the hall of my Fathers, art gone to decay;

In thy once smiling garden, the hemlock and thistle

Have choak’d up the rose, which late bloom’d in the way.– Lord Byron, “On Leaving Newstead Abbey”

Poetry is dead.

Any essay whose opening paragraph consists of a three-word sentence stating a non-obvious universal is either going to be a short essay or is going to spend the next paragraph walking back the provocative sentence into something more nuanced and specific. The technique is the literary equivalent of clickbait, or a catchy headline being shouted on the street corner, and readers are quite justified to be cautious of essays that start that way. But, it’s somehow an appropriate technique in this context. Poetry is all about hyperbole and metaphor, about connecting concrete images to abstract ideas; poetry is all about strong, emotionally charged statements which might not be literally true.

Or at any rate, poetry was about all those things. Because, as I mentioned before, it’s dead now.

Part II: Will Any Age Forget the Fleece?

For many linguists, Latin is the canonical, go-to example of a dead language. Wikipedia lists it as the first example of a ‘dead’ (as opposed to ‘extinct’) language, citing the Oxford Dictionary, which says the same thing. Global Language Services says that “Latin is probably the most widely known dead language”, and just a simple Google search for the phrase “dead language” will turn up ‘Latin’ as the very first result.

Putting ‘Latin’ in bold when it wasn’t even searched for is just rubbing salt in the wound.

Putting ‘Latin’ in bold when it wasn’t even searched for is just rubbing salt in the wound.

For many speakers of Latin, the assertion “Latin is a dead language” is the canonical, go-to example of why linguists don’t know what they’re talking about. Reading through the aforementioned search results, you find articles such as “Look, Latin Is Not Useless, Neither Is It Dead”, or “Why Latin Isn’t Dead”. AncientLanguage.com answers the question “When Did Latin Die?” with “never” and “Is Latin a Dead Language?” with “no”. Babble.com’s article concedes that it is “Technically Dead” in one header, but immediately clarifies “But It’s Also Sort Of Alive” in the next. /r/Latin declares that if Latin is dead, they’re all necromancers (which lines up with every horror movie which has ever featured ominous Latin chanting), or will flippantly respond that the language is not dead but simply Roman around.

And these aren’t just baseless claims. On the religious side, Latin is the official language of the largest organized religion in the world, and more than five hundred Masses are said in Latin every week just in the United States. On the academic side, classicalstudies.org lists almost a hundred Classics Departments offering graduate programs in North America for academics, and for hobbyists there are numerous online communities, long-running podcasts, and YouTube channels devoted to or entirely in Latin.

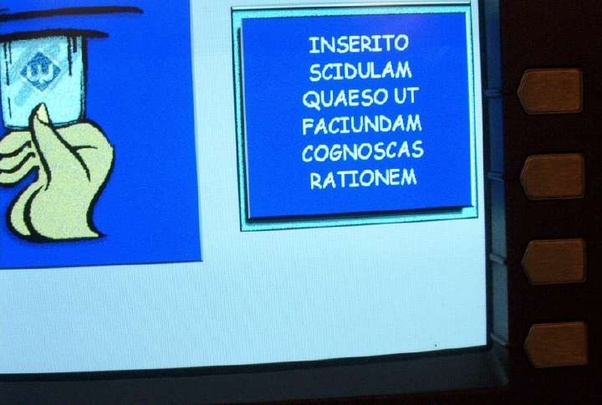

Can a language truly be dead if it has an ATM?

Can a language truly be dead if it has an ATM?

But intuitively, there has to be some validity to the declarations that the language is dead, despite all of the religious, academic, and casual devotees. Latin is clearly in a qualitatively better position than Linear A, which as of 2022 no one on Earth can even decipher, let alone speak. But it’s just as clearly in a qualitatively worse position than English, the de facto lingua franca of most of the world. The difference can’t just be the relatively small number of speakers; the Icelandic language only has around three hundred thousand native speakers compared to English’s three hundred million, but Icelandic is completely alive, or at the very least more than 0.1% as alive as English. It’s possible that Latin actually has more speakers worldwide than Icelandic does (depending on how you count), but it’s still in a different category. Dead or not dead, there’s something Icelandic is that Latin isn’t.

And the difference can’t even be the fact that English and Icelandic have native speakers while Latin has none. Four hundred years ago, Latin still had no native speakers, but its situation was not at all the same as today. If you were in Europe in the 17th century, and you wanted to understand or contribute to any form of science, you had to know Latin; ditto to get into any university or seminary. Isaac Newton may have been an Englishman, but he called his most important book Principia Mathematica and not Principles of Mathematics because otherwise, most natural philosophers outside of England itself would not have been able to read it.

That’s the biggest qualitative difference: in the 17th century, there was a broad category of things which were not themselves Latin-related, but which could only be done if one knew the language. In the 21st century, there isn’t. Catholics in 2022 can attend Mass in Latin, but they can just as easily attend Mass in English - even the link from earlier to the Catechism of the Church in Latin has its URL in English. You might be able to find a copy of Catus Petasus, but it’s easier to find it by the original title of Cat in the Hat. Ultimately, you can learn the language, but you’re ultimately learning the language either a) for its own sake, or b) for necromancy. Anything else, you can do with a different language.

Part III: Thou Shalt Kindle By Night

A lot of reasonable objections to the assertion that poetry is dead look pretty similar. EventBrite in 2022 lists over a thousand poetry slam events in various locations; the Poetry Foundation website has around a million page views a day. The national “AP English Literature And Composition course has three of its nine core units centered on poetry, and over three hundred thousand students in the US take it every year. Superhero cartoon franchises have multiple episodes named after the same William Blake poem, TVTropes has an entire category of haiku summaries, and an online programming competition in 2019 decided to host a poetry challenge in parallel for the sheer fun of it. There’s clearly a decent amount of poetry still being read, heard, and written in the English language. So why call it dead?

The most well-known English translation of Goethe’s German play Faust was translated by Bayard Taylor in the 1850s, and he spent most of his preface talking about why he translated the play into verse and not into prose, like most of the existing translations of his day had done. The core of his reasoning was that “Poetry is not simply a fashion of expression: it is the form of expression absolutely required by a certain class of ideas.” According to Taylor, it was impossible to truly understand the concepts and emotions Goethe was trying to get across merely by reading a prosaic translation, no matter how accurate.

Wait. A whole class of ideas can only be expressed through poetry? Poetry is that fundamental to human communication?

Percy Shelley went a step further in a set of essays about poetry written a few decades earlier earlier, saying that poets (in terms of lasting impact on the world) fundamentally stand above “scupltors, painters, and musicians” in the same way that a harp stands above a guitar in lasting beauty, and that even people like great political or religious figures who do have more fame than poets don’t really deserve it. It summarizes its main point on the importance of poems and poetry by saying that “Poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the world”.

But okay, we’ve already acknowledged that poets love hyperbole and exaggeration for effect, and Taylor and Shelley were both poets. Of course they’d be inclined to hype up the importance of their own fields. What did non-poets used to think about it?

Back in the 1970s, Clyde Hyder wrote a very interesting book about the poet Charles Swinburne, and spends a large part detailing the history of Swinburne’s most famous book, Poems and Ballads, and the most famous poem in it, “Dolores”. In 1866, Swinburne had already produced several controversial books, and had been received harshly by the poetry columns in such papers such as Gentleman’s Magazine and Fortnightly Review. As such, he was already on thin ice, and when he finished Poems and Ballads his publisher, J. Bertrand Payne, decided to withrdaw it, after hearing that The Times and The Edinburgh Review were going to attack the book. Still, Swinburne was undeterred, and switched to a more shady publisher named John Hotten (who was much more agreeable to controversial subject matter), and in August of 1866 his publisher released Poems and Ballads.

The critical response was swift and severe. The first Saturday after the book came out, John Morley (writing anonymously for the Saturday Review) called the book Swinburne’s way of “grovelling down among the nameless shameless abominations which inspire him” and “glorify[ing] all the bestial delights that the subtleness of Greek depravity was able to contrive”, concluding that the book’s only redeeming virtues were the quality of its verse and that the Greek metaphors were going to be unintelligible to a great many people, which would hopefully cause them to not buy or read it. That same day, Robert Buchanan (writing anonymously for the Athenaeum) called it “unclean for the sake of uncleanness” and “a poet degraded from his high estate, and utterly and miserably lost to the Muses”. And also on that same day, an anonymous author reviewer writing for the London Review called the book “conscious revelling in the actual sense of evil”, described “Dolores” as “a mere deification of incontinence”, and is glad that Swinburne seems to have gotten inspiration from France so that Great Britain could wash her hands clean of the whole matter.

This continued throughout the year; Buchanan wrote another critical piece for the Spectator a few months later, and Henry Morley (no relation, so far as I can tell) wrote a piece for the Examiner around the same time supporting the work. Swinburne came out to defend his poems himself in an independently published pamphlet in November, saying that that his were young mans’ poems, not suitable for the teenaged girls these squeamish reviewers evidently were; the Pall Mall Gazette and the Quarterly Review didn’t find this explanation satisfying enough, and Punch in November summarized the general sentiment among English critics by saying that Swinburne ought to “change his name to what is evidently its true form - SWINE-BORN”.

When the controversy reached the United States in November, Swinburne’s friend William Rossetti wrote a piece defending Swinburne for the North American Review, but after seeing JR Lowell’s scathing critique, decided to publish his defense as a book instead. The New York Times condemed the book as possesing the lowest lewdness, while John Morley’s review from August was reprinted in the Eclectic Magazine and the anonymous London Review critique was shown in Littel’s Living Age. It wasn’t all negative, though; The Nation and Galaxy both contained mixed but overall positive reviews of the book, and back in England, Fraser’s Magazine, which had been very critical of Swinburne’s two earlier books in 1865, came out in his favor. Over the next few years, the immediate controversy died down; even John Morley (who Swinburne eventually figured out wrote that first critical piece) wrote a piece praising an unrelated Swinburne essay, but the damage had been done in other areas and with other people. Robert Buchanan actually ended up suing the Examiner for publishing a Swinburne poem libelling him, which Swinburne only wrote in retaliation to a poem attacking him he thought Buchanan wrote, but which was actually written by the Earl of Southesk. It wasn’t until the early 1900s that the literary world generally held Swinburne in favor.

When I first read this history, what surprised me wasn’t the notion that an artist might produce a controversial work and experience both critical backlash and publisher cancellation in response. What surprised me was the sheer number of newspapers that had poetry columns! The Athaenaeum was specifically a poetry journal, to be sure, and a few like the London Review were at least literary magazines, but Fraser’s Magazine? The New York Times? Many of these papers were general-interest publications covering a wide variety of topics which thought this one poem worth covering. And these weren’t short columns, either - the three initial Saturday critiques of the poem averaged twenty-five hundred words, which even for newspapers would have been a significant investment of space. Poets and critics believing their work to be deeply important is one thing, but this was widespread poetry controversy that stretched to multiple countries, which presumably every single publication involved thought its audience would be willing to pay to read about.

Like Latin, poetry has its hobbyists and writers and academic studies and journals. Most English-speaking readers would recognize a limerick as a limerick, and most probably know that haikus require five syllables, then seven, then five. But like Latin, there is clearly some qualitative difference between the scope of poetry now and the scope a hundred and fifty years ago, because no poem published now would attract anywhere near this much attention. Other art forms certainly could receive that much criticism in popular venues - 2500 words pales in comparison to MauLer’s review of The Last Jedi, which at five hours and change was twice as long as the movie itself - but a poem will not. Poems can attract ire and editors can issue retractions, but it’s all within literary circles; Anders Carlson-Wee’s 2018 poem “How-To” was eventually pulled back by its publisher, The Nation, after a “social media storm”, but searching Google Trends for the author’s name results in half the analysis fields saying “your search doesn’t have enough data to show here”, so the social media reaction was at most a tempest in a teacup.

It’s hard to even imagine poems written in 2022, good or bad, being as widely viewed or cared about as an average movie. And yet, at one time, they were. What changed?

Part IV: Golden with Wastage of Gold

Old King Cole

Was a merry old soul

And a merry old soul was he

He called for his pipe

and he called for his bowl

and he called for his fiddlers three.

It’s not always true that art forms always progress from simple to complex; TVTropes has certainly collected enough examples to prove that the earliest take on a motif or story can be complex and nuanced in its own right. But it is true that the first artist to use a trope has no previous examples of it to build on, and the second artist does. The second artist, in fact, must build on it, or alter it, or start somewhat differently, because unless you’re Pierre Menard writing Don Quioxte you can’t write an story identical to one that’s already well-known and be received as anything but a plagiarist. And the more times a trope is used, the further from the baseline idea an artist needs to go to be counted as ‘original’, if originality is the goal.

After W.B. Yeats:

Of an old King in a story

From the grey sea-folk I have heard

Whose heart was no more broken

Than the wings of a bird.As soon as the moon was silver

And the thin stars began,

He took his pipe and his tankard,

Like an old peasant man.And three tall shadows were with him

And came at his command;

And played before him for ever

The fiddles of fairyland.And he died in the young summer

Of the world’s desire;

Before our hearts were broken

Like sticks in a fire.

The same is true for audiences. When Superman lifted a car over his head in 1938, that was enough to launch a series of comics that put an entire genre of stories into the public consciousness for decades. When Scarlet Witch threw a car with telekinesis in 2016, it’s just one part of a much more elaborate fight scene, hardly worth singling out for mention unless doing a play-by-play. A man lifting a car can still be an exciting moment in the context of a good story, but there has to be a good story around it. Almost no superhero afficianado would pick up a new comic solely on the basis of “So get this - there’s this guy, who can PICK UP A CAR!”. So, authors seeking to make a mark have to branch out further.

And having prior work isn’t only a restriction on creativity, either; it can just as easily enable work that couldn’t have been written otherwise. An audience in 2000 wouldn’t be impressed by a superhero whose only distinguishing feature was being strong enough to lift cars, but an audience in 1938 wouldn’t know what to make of M. Night Shyamalan’s film Unbreakable. The fact that the film was in color and the crispness of the picture and music would have been quite impressive, but much of the plot and dialogue would have made little sense; M. Night Shyamalan assumed that his audience would have the shared cultural experience of sixty years of comic books and superheroes, and wrote accordingly. The question of “how would people with superpowers act in a world like ours, instead of a comic book world?” isn’t a terribly interesting question to ask if there aren’t well-known comic book worlds to compare it with.

After Swinburne:

In the time of old sin without sadness

And golden with wastage of gold

Like the gods that grow old in their gladness

Was the king that was glad, growing old:

And with sound of loud lyres from his palace

The voice of his oracles spoke,

And the lips that were red from his chalice

Were splendid with smoke.

But if new works have to build on the old, then what stops all art from becoming incomprehensibly complex? Ultimately, it’s the same pressures. Audiences will only be willing or able to read or watch so much prior work; there’s a limit to how much knowledge can be assumed for any audience, and so eventually any author trying to use allusions and metaphors and references as a foundation for his work must either cut off much of his potential audience, or explain the background using time that could be used to further the plot. A “Previously On” segment in a TV show, even if it’s Dragonball Z, can’t reasonably take up the entire episode, and certainly can’t take up more than that.

For some authors, complexity is the entire point. Scott Alexander’s Unsong is a book in a fictional setting in which obscure and unlikely coincidences and references are fundamental to the laws of physics, and which by necessity is filled with jokes that span a dozen dead languages, and as much obscure etymology and history as it does plot or dialogue. This was the entire point; the author in response to a question said that it was written in part “as the beginning of a rabbit hole that can be followed arbitrarily far, without a predetermined end, until eventually it even goes out of the text itself”. Anybody who wanted to go a step further in that direction, and build off that work, would have to be even more well-read and even more persuasive and engaging, or else lose just about all of the potential audience in a maze of metaphor.

After Lord Tennyson:

Cole, that unwearied prince of Colchester,

Growing more gay with age and with long days

Deeper in laughter and desire of life

As that Virginian climber on our walls

Flames scarlet with the fading of the year;

Called for his wassail and that other weed

Virginian also, from the western woods

Where English Raleigh checked the boast of Spain,

And lighting joy with joy, and piling up

Pleasure as crown for pleasure, bade me bring

Those three, the minstrels whose emblazoned coats

Shone with the oyster-shells of Colchester;

And these three played, and playing grew more fain

Of mirth and music; till the heathen came

And the King slept beside the northern sea.

Patrick Hannahan’s Gigamesh takes that last step further, being a response to and one-upping of James Joyce’s famously complex Ulysses with its detail and layered references. There are more than ninety-seven different meanings to the fact that the title does not contain the letter ‘L’, the length of each of the thousand words in Chapter I form the first thousand digits of π, the letters of each word in Chapter II forms a musical composition for a song based on three different tellings of the Faust legend, the pattern of commas in Chapter VI forms the map of Rome, and these references and riddles and codes pile on and on during each successive chapter until ultimately, Gigamesh is so dense that it can’t possibly exist. Which, of course, it doesn’t. Whatever limit there is on how much information can be packed into one space, Gigamesh is far beyond that limit. There’s only so far you can actually go.

Genres or mediums can go on getting more intricate and involved for a while, so long as existing audiences find it worthwhile to stay and new audiences find it worthwhile to learn and catch up, but not forever. There’s always a limit to how much an audience can get from a work of art, and how much meaning an author can express. Similarly, there’s always a limit on the use of tropes: too esoteric, or too meta, or too otherwise detached from the original patterns, and audiences can no longer understand how the new work connects to the old. And the closer to those limits an author or a genre gets, the harder it is to appeal to a fresh audience, and the less comprehensible it will be to the uninitiated reader.

After Robert Browning:

Who smoke-snorts toasts o’ My Lady Nicotine,

Kicks stuffing out of Pussyfoot, bids his trio

Stick up their Stradivarii (that’s the plural

Or near enough, my fatheads; nimium

Vicina Cremonce; that’s a bit too near.)

Is there some stockfish fails to understand?

Catch hold o’ the notion, bellow and blurt back “Cole”?

Must I bawl lessons from a horn-book, howl,

Cat-call the cat-gut “fiddles”? Fiddlesticks!

In 1913, Ezra Pound laid the groundwork for the English poetic movement which would later be called “Imagism” with an essay “A Few Don’ts by an Imagiste”. In the essay, he railed against the stagnation he saw as happening in poetry, and set as a new standard a number of artistic choices which would come to define 20th century poetry. One such choice was free verse (poetry without either rhyme or metre), though he advocated for poets to know the intricacies of rhyme and metre even if they never used them. Another choice was that of eschewing all abstract imagery in favor of the concrete; talking about “the dim lands of peace” didn’t heighten the reader’s understanding of “peace”, but dulled the reader’s understanding of “the dim lands”. Rhyme and metre were a set of training wheels, suitable for gaining an understanding of language and of poetry, but too constraining to use indefinitely. English poetry had ridden with these training wheels for four hundred years, and was long past ready to take them off.

Ezra Pound’s advice caught on quickly; by the 1950s, Imagism’s various descendants had become the dominant force in poetry in the English-speaking world. Pick up any English poetry journal published in the fifty year period between 1970 and 2020, and virtually all of the poems will be in something like free verse. And since free verse almost by definition rejects standard patterns and constraints, the far more subtle patterns possible to include with free verse will by nature by far more difficult for the layman to read and appreciate. And so, those modern poetry journals can publish any number of controversial poems without the controversy ever reaching the mainstream - one writes a poem in a journal for the sake of writing a poem in a journal, to be read by other poets, and not to be read by the public.

After Walt Whitman:

Me clairvoyant,

Me conscious of you, old camarado,

Needing no telescope, lorgnette, field-glass, opera-glass, myopic pince-nez,

Me piercing two thousand years with eye naked and not ashamed;

The crown cannot hide you from me,

Musty old feudal-heraldic trappings cannot hide you from me,

I perceive that you drink.

(I am drinking with you. I am as drunk as you are.)

I see you are inhaling tobacco, puffing, smoking, spitting

(I do not object to your spitting),

You prophetic of American largeness,

You anticipating the broad masculine manners of these States;

I see in you also there are movements, tremors, tears, desire for the melodious,

I salute your three violinists, endlessly making vibrations,

Rigid, relentless, capable of going on for ever;

They play my accompaniment; but I shall take no notice of any accompaniment;

I myself am a complete orchestra.

So long.– GK Chesterton, “Variations on an Air”

Part V: The Unfelt Hands of Time

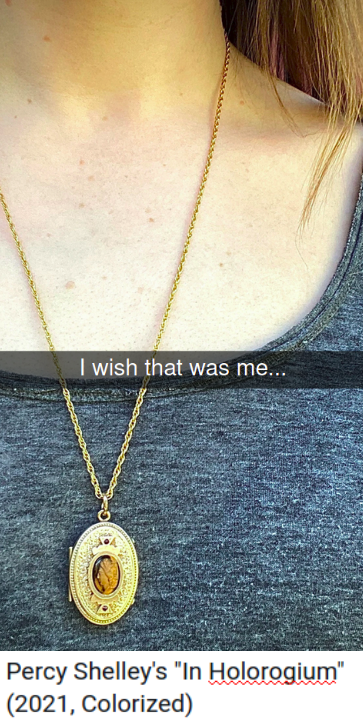

Inter marmoreas Leonorae pendula colles

Fortunata nimis Machina dicit horas.

Quas MANIBUS premit illa duas insensa papillas

Cur mihi sit DIGITO tangere, amata, nefas?– Percy Shelley, “In Horologium”

A while back, while reading late at night, I stumbled upon an obscure Percy Shelley poem in an anthology which in English would be titled something like “About the Clock”: only four lines long, but in Latin, and in oddly phrased poetic and grammatically imperfect Latin to boot. There was no translation provided, and a quick Google search turned up no English translations at all, anywhere on the Internet. So, I got out Whitaker’s Latin and after twenty minutes painstakingly rendered the first half as:

Between the mountains, the exceedingly fortunate machine hanging down

Tells the marble-like hours to Leonora.

This was an accurate, literal rendition of the first two lines of the poem, but it told me nothing; knowing what it said didn’t give me any clue as to what it meant. So, I messaged Felipe (unphased by an unexplained Latin message at half past midnight), and between my Latin book and his fluency in Spanish, we translated the second half over another twenty minutes. Starting, of course, with the puns. pendula is used as a verb meaning hanging down, but given the context it also calls to mind an old-fashioned pendulum clock. digito means literally a fingerwidth and is used the way we’d use the phrase “by a hair’s breadth” (to represent two things extremely close together), but its literal meaning of finger goes well with the previous line talking about the clocks’s hands (manibus). And suddenly, it clicked: this is a dirty poem! The literal translation of the next two lines, tweaked in light of this, started to make sense.

That [the machine] presses hands, unnoticed, to two breasts -

Why is to touch a hair’s breadth away, beloved, a sin to me?

What was Shelley saying? He’d probably seen (or thought of) a pretty girl wearing a French watch on a locket, and being 17, was of the perfect age to get very jealous of the watch. So he wrote a poem saying as much. And, buried as “In Horologium” was (it was only published decades after his death), nobody except one 1872 anthology writer even bothered speculating about it. It was immensely satisfying, both to be the first ones to appreciate it in probably a very long time, and to to realize that the thing we were appreciating was stupid teenaged humor.

But that’s exactly the point - it was satisfying because we were the only ones to do it. It’s that gap, those forty minutes of painstaking translation before the “aha!” moment, that marks the difference between a dead language and a living one. We had to go far outside of what we normally read to get it, and the fun of discovery was as much a motivator as the actual quality of the poem itself. This is fantastic, but it doesn’t scale; if we sent this poem to a dozen other people, chances are that none of them would care to the extent that we did. If we wanted to share it at all, we’d have to include some kind of translation:

The luckiest clock to ever tell the time

Adorns the marble mountains of Lenore.

Its hands caress, and always you ignore –

Why is it such a sin, beloved, for mine?

But that translation lacks the puns with ‘pendula’ and ‘digito’, and even aside from the puns, it falls nearly as flat as the literal translation does. It gets the message across, but it has no weight to it; you’re certainly not going to see it go viral. A poem with a literal translation just isn’t going to be sufficiently ‘alive’ to capture the humor in the original. The actual translation into modern art would be a different form of art altogether:

And a year, that meme will be dead too.

Part VI: And What Shoulder, And What Art, Could Twist the Sinews of Thy Heart?

There’s a glaring omission in my analogy comparing poetry to Latin: Latin didn’t simply die out, but changed. All of the Romance languages (Spanish, French, Italian, Portugese, Romanian, and a host of minor languages) directly descend from Latin, and even the European languages which don’t, such as English, have a copious supply of words and phrases derived from the language. Fr. Foster, probably the greatest Latinist of the early 21st century, was fond of saying that if one knows Latin, one can learn French or Spanish in a weekend, and though he was exaggerating, his point was pretty clear. Latin’s children and more distant relations live on, throughout the world - why call it dead?

But, Felipe is fluent in Spanish, and it still took him some time to parse through “In Horologium”. Had he tried to read it assuming it was Spanish, he’d have come away with the conclusion that Shelley barely knew Spanish at all and wrote a bunch of vaguely comprehensible gibberish. Without knowing that the poem was in a dead language related to his living one, there would have been no possibility that he’d appreciate it or enjoy it to any degree - it would have seemed, at best, like defective Spanish.

Likewise, poetry has various offshoots and descendants, some more alive than others. Certainly music is alive and well in the English-speaking world; there are a countless number of genres and subgenres and variations on style, and tens of thousands of bands making new music. Wikipedia spends nearly a thousand words to explain the notion of musicians ‘selling out’…and another five thousand words in the now-archived Talk Page to debate precisely which musicians should be included in that list. The conventions of rhyme and metre vary significantly from genre to genre, and all are different than the conventions of traditional poetry, but it’s clear that something of poetry exists in art forms which are very alive.

But the problem is the same as Latin. Someone familiar with modern music who read a sonnet as if it were meant to be sung aloud with instruments would come away with the conclusion that the sonnet is at best a defective song. The rhythms of poetry emerge from the patterns of stressed and unstressed syllables in the words themselves, while in music the stresses in the syllables are secondary to the rhythm of the instruments. Trying to sing a typical English poem to musical accompaniment will sound as awkward as trying to read a set of lyrics aloud - one can appreciate one art form, or the other, or both, but interpreting one art form through the conventions of the other is a recipe for incomprehension.

And that’s a word at the heart of both poetry and music: convention. Too loose, and an audience doesn’t know how to understand the work. Too tight, and there’s no room for innovation. Audiences pick up conventions implicitly and never give them a conscious thought, or debate them explicitly to great detail, but trying to understand art with no conventions at all, and no understood common ground between artist and audience, is the same thing as if the artist spoke one language and the audience another.

Part VII: From Page to Page, From Book to Book

When Bayard Taylor translated Goethe’s Faust in the 1850s, he spent most of his preface talking about why he translated the play into verse and not into prose, like most of the seventeen existing translations of his day had done; according to Taylor, it is impossible to understand the concepts and emotions Goethe was trying to get across merely by reading a literal prosaic translation, no matter how accurate. It couldn’t be just any kind of poem, either. Goethe himself, asked about the possibility of translating his work, said that the kind of rhythm and metre needed to accurately convey the story he was trying to tell varied considerably depending on which language his work was going to be translated in. French was going to be an uphill battle from the getgo, but as English and German were a close relation, he was more optimistic, and could definitively rule out some styles - translating his flowery and sincere “Roman Elegies” into English in the comedic style of “Don Juan” would have an “atrocious effect”. But when asked about for particulars, all he could say was:

The rhythm is an unconscious result of the poetic mood. If one should stop to consider it mechanically, when about to write a poem, one would become bewildered and accomplish nothing of real poetical value.

If Goethe and Taylor were at all serious, then taking apart every word of every stanza, and picking the perfect phrase to not just convey the meaning but convey the verse, was always going to be an immense challenge…and after nearly two decades of work, Taylor succeeded. When I first tried to read Faust, I was bored and confused; the constantly shifting rhyme scheme was jarring, the word choices were confusing, and it didn’t seem to have any structure or patterns. I couldn’t understand why other people thought it was so great, and more importantly, it never occurred to me that I was missing a piece of context that others had. I just wrote it off, and assumed it was overhyped.

Then one day, on YouTube, I stumbled upon the 2000 Peter Stein production of Faust (original video sadly removed, but a partial playlist is still around) performed, in German, as a stageplay and as true to the original as possible. (So true, in fact, that various German critics reputedly panned it for being “too much Goethe, too little Stein”). I don’t speak German and the video had no subtitles, so on a whim, I put Taylor’s translation on one screen, the play on the other, and tried to follow along. Stage directions and scene transitions helped greatly, certain names and proper nouns common to both English and German helped keep me in sync, and over the course of an hour, I was able to follow along in broad strokes, and avoid getting bored the way I had the first time.

Midway through scene II, at just over an hour in, something clicked, and I got it. I don’t know what changed, but I could almost feel the flow of the actors’ speeches, and the wildly varying rhyme scheme in Taylor’s translation all just fit together, and felt right. I’d been trying to read it as a poem, and not speak it as a stageplay; the verses were at some middle ground halfway between speech and song, and in only trying the latter I’d missed the subtleties. Reading the translation was no longer a chore at all, and after six hours of reading and watching I found that I could even speak impromptu stanzas in that same rhyme and metre on the fly; they weren’t terribly good, but for a few moments it was as if I wasn’t reading English or listening to German, but reading and hearing and speaking some new language with the words of the former and cadence of the latter, invented just for the play. And if I had to translate that language into normal speech, I’d say it couldn’t be done.

Part VIII: Must Springtime Fade?

None is travelling

Here along this way but I,

This autumn evening.– Basho, “About Fifty Haiku”

I’d say that accurately translating Goethe and Taylor into English speech couldn’t be done, but more counterintuitively, I’d also say that translating it into English poetry couldn’t be done either…even though it already has been. Goethe was concerned about translating his more serious Elegies into comic verse; he knew that comic verse couldn’t convey what he meant. What I argue is that all poetic forms in English, such that they are, are now comic verse.

The English haiku is very different than the Japanese haiku, despite being structurally similar (17 syllables in a 5-7-5 pattern), due to more esoteric requirements. A haiku in Japanese, traditionally, has to include a kigo (a word or phrase which implies the season the poem takes place in), a kireji (a word that brings a natural end to a line, the equivalent to a caesura in Western poetry), and critically, the kigo is supposed to be an image of nature. These were important enough that the Japanese actually had a different word, senryu, for poems which had the structure but were not about nature, and which didn’t include a reference to the season.

But it would sound weird if one were to write an English haiku about nature in most contexts for the general public, with no jokes or hidden ironies. Fundamentally, the haiku in English is a primarily light verse, with a light-hearted topic matter, often including a meta reference to the limitations of the syllable count, or finding a bulky five-syllable word like ‘refrigerator’ to take up an entire line on its own. The style and structure of a poem is more than just how many syllables go in a line and which rhyme goes where; the tone and topic matter are just as important to the expectations of the audience. The kireji is not just absent, it’d actively go against the style of an English haiku. At most, you might see these requirements included as a joke, as in a random Reddit Minecraft newsletter:

Mumbo posts thumbnail.

One hundred duplicate posts

Blossom like spring leaves.

Haikus aren’t alone in this stylistic requirement. For a few years, a Tumblr user named Erik Didriksen wrote a series of “Pop Sonnets”, taking modern pop music and translating them, roughly, into Shakespearean sonnets, down to every requirement of rhyme and syllabic stress. And as a blog, it worked…because they were funny. The notion of taking a stuffy art form like a sonnet and putting modern words to it, of reading “Monster Mash” written in iambic pentameter, was inherently silly; Erik in an interview described the fun of mixing archaic language with modern slang: “with all the thees and thous preceding it, you get a laugh from the sudden, unexpected modern turn of phrase”. And so the Tumblr account was quite popular during its run; by comparison, a year-long run of daily non-comedic sonnets on Twitter produced some decent poems, but nothing so memorable, and certainly nothing so popular, as Pop Sonnets.

(This is not to say that Shakepseare’s work was all serious, not by any stretch - but only the less serious aspects could be captured in Didriksen’s work.)

The most popular English poet on the Internet in 2022 is probably /u/poem_for_your_sprog, who also holds the distinction of posting just about all of his work in public fora which are not about poetry - one of my earlier criteria for an art style being alive. He’s averaged a poem a day for a full decade with a devoted following, and perusing his archives will show perhaps nineteen poems out of twenty as being short and light-hearted, well-written in a variety of metres to get a chuckle out of passing readers. He writes with all varieties of meters (including the odd sonnet here and there), and the average Internet reader can understand it and smile…but he can’t write a poem that’s sincere without losing the audience altogether. There are expectations every poet in every context is bound to, and to break them generally goes as well as a goldfish breaking its containment and making it out into the open air.

But if /u/poem_for_your_sprog made the mistake of listening to me and believing me when I say that ‘poetry is dead’, he’d never write that one poem in twenty, and Reddit would be just a bit dimmer for it. By any of my definitions of a ‘living’ art form or a ‘living’ language, his work would have the spark of ‘life’ in it: the ability to convey thoughts that couldn’t be conveyed otherwise. And perhaps the other nineteen out of twenty, the ‘normal’ poems, are precisely why he can write the twentieth. Perhaps, as poetry shifted lighter and lighter, sincere poetry needed to cloak itself in humor, as a sort of protective mimicry in order to survive.

If that’s possible, perhaps translation isn’t impossible either.

Part IX: Oft of One Wide Expanse Had I Been Told

So, the big question is…can it be done? If poetry in all its traditional forms is dead, can it be “translated” into forms of art still very much alive?

I truly don’t know. There have been a number of impressive translations of poetry from one language to another or one form to another, over the years. Speaking just about translations to English, Taylor brought Goethe’s Faust in from German, and Chapman brought Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey in from Greek (to the delight of poet John Keats). FitzGerald’s translation of Omar Khayyam’s Rubaiyat from Persian was at one point one of the most popular books of poetry in the English language, and Michael Kandell’s translation of poems from Stanislaw Lem’s Polish sci-fi novel The Cyberiad are singularly impressive works of constrained writing in their own right:

“Have it compose a poem — a poem about a haircut! But lofty, noble, tragic, timeless, full of love, treachery, retribution, quiet heroism in the face of certain doom! Six lines, cleverly rhymed, and every word beginning with the letter s!!”

“And why not throw in a full exposition of the general theory of nonlinear automata while you’re at it?” growled Trurl. “You can’t give it such idiotic—”

But he didn’t finish. A melodious voice filled the hall with the following:Seduced, shaggy Samson snored.

She scissored short. Sorely shorn,

Soon shackled slave, Samson sighed,

Silently scheming,

Sightlessly seeking

Some savage, spectacular suicide.

But not all of these were as literal as Taylor’s Faust. While Lem’s original poem in The Cyberiad was equally constrained, the original constraints and subject matter were entirely different, even down to a different letter (Lem’s original had only words starting with ‘c’). As another blogger put it, Kandell’s version was “not really a translation at all, although it was Lem who created the situation within which this exercise had meaning”.

And FitzGerald took similarly large liberties with Rubaiyat. Where a literal translation from Persian of quatrain 33 might go:

The heavenly vault is a girdle (cast) from my weary body.

Jihun’ is a water-course worn by my filtered tears.

Hell is a spark from my useless worries.

Paradise is a moment of time when I am tranquil.

FitzGerald translated it as:

Heav’n but the Vision of fulfilled Desire,

And Hell the Shadow from a Soul on fire,

Cast on the Darkness into which Ourselves,

So late emerged from, shall so soon expire.

(Clement Wood, in his invaluable 1936 Complete Rhyming Dictonary and Poet’s Craft Book, somewhat amusingly described this line as “Oriental impassivity and superiority to things earthly have been replaced by a viewpoint accurate enough to have come out of Freud, and acceptable as concentrated truth to many of us”, a description which may have aged faster than the poem itself.)

Part X: By My Black Hand, the Dead Shall Rise

Or maybe it isn’t a matter of precise wording at all, but simple quantity. Maybe, with all of the other forms of entertainment that exist today, poetry isn’t the staple food that it once was, but could still be a spice, sprinkled here and there to liven up the taste. Stephen Moffat tried this idea throughout his run of Doctor Who, with a poem in the style of nursery rhymes opening the episode “The Beast Below”, a whole series of connected stanzas in the second half of Series 5, and a whole group of monsters that exclusively spoke in rhyme in “The Name of the Doctor”, all to contribute to the fairytale atmosphere he was going for. Eight years earlier, Neal Stephenson had the same goal and same idea in his Diamond Age, using a poem to write an epiptath in the metaphor of a children’s book. Unsong went a step further and titled every chapter after lines from William Blake poems, along with quoting dozens of poems within the main thread of the plot and dialogue.

DC Comics’ demon-hero Etrigan usually speaks in rhyming iambic tetramer, and this simple character trait was enough to get him an appearance in at least three animated movies and three other animated TV shows. YouTube comments on his various appearances tend to like the appearances where he rhymes and dislike the appearances where he doesn’t, saying in the latter case that it’s a waste and a loss of something interesting, in much the same way that DC’s iconic Green Lantern Oath would clearly lose something if rendered as prose:

“In brightest day, in blackest night,

No evil shall escape my sight.

Let those who worship evil’s might

Beware my power: Green Lantern’s light!”

Poetry was once common, and now isn’t. Poetry once rhymed, and now doesn’t. Poetry was once alive; this, you could scarcely call living. But human nature doesn’t change, and insofar as Taylor and Goethe and Shelley were right, insofar as there is some part of the human experience that can only be expressed in verse, people will keep looking for ways to express it. Some of that expression - most of it, probably - is in music, which could plausibly claim to replace poetry the same way color films replaced black-and-white. But not all. The gap between the past and the present is huge, but not uncrossable. There should always be a niche, in some corner of culture, for obscure authors and their obscure poems, both new and old.

In fact, one of those obscure authors, and obscure poems, comes to mind now. “That is not dead which can eternal lie”, I think it went. “And with strange aeons even death may die.”