You have probably heard of Advent of Code. Every single year, Dave, my friend and fellow coauthor, stays up till midnight every day, trying to get on the leaderboard. Sometimes he also writes poetry about it. He’s done so religiously for over a decade. In fact we started our Rust journey with Advent of Code.

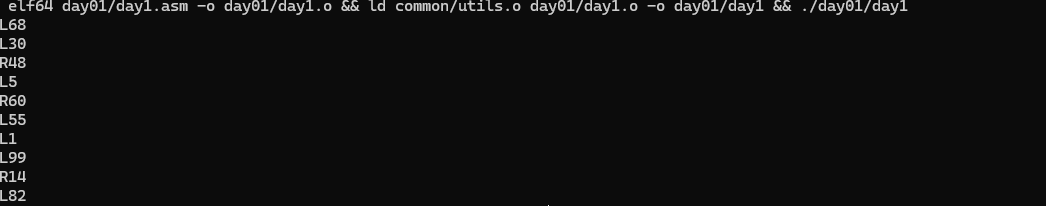

This year, I was somewhat relieved. After a decade of effort Eric Wastl had decided to cut Advent of Code back to twelve days. That meant that this year I had a chance of finishing. (A feat I’ve only achieved once before). Twelve days is about what I tend to have bandwidth for. So, with a screaming newborn in my life, and inspired by certain challenges 1, I said “why not roll two things into one? I’ll learn assembly and do advent of code!”.

That, dear readers, is called hubris and how I descended into the very pits of hell.

Canto 1. The Forest of Syscall

Midway upon the journey of our life

I found myself within a forest dark

For the straightforward pathway had been lost. 1 2

Descending into the abyss, of course, never starts with a plunge into a dark pit3. No, you start by deciding that all you really need to do to begin is parse an input. Sure, normally you’d just call something like read_file, pass in a path, and call it good, maybe having to do a little finagling with your path before things worked. If your language is picky you might have to remember to close the file. It couldn’t be that different in assembly right? A file is just a collection of bytes somewhere in storage. All we have to do is load those into memory and we’d be golden.

Sure, we have no file object, not even a file object name, all we have is a File Descriptor, a raw integer, which we have to conjure ourselves through the magic of syscall. All we need are three simple calls, open, read and close. Like Dante, I had my Virgil, in this case Claude, who I often asked insightful questions like “what the heck do the magic numbers I’m passing to syscall mean” (identifying which command i’m running) and “why does it work that way?” (someone in 1970 decided it was a good idea).

So, being a good developer, I decided i’d make a utility file, which we’d surely keep up to date with all kinds of functions we’d use throughout our cheerful christmas journey. The road to Hell is paved with good intentions. The code to actually read a file is not bad

read_file:

mov rax, 2 ; syscall 2 = open

mov rsi, 0 ; read-only mode

syscall

mov [file_descriptor], rax

mov rax, 0

mov rdi, [file_descriptor]

mov rsi, input_buffer

mov rdx, 32768 ;32kb, plenty of memory

syscall

mov r8, rax

mov rdi, rax

mov rax, 3

mov rdi, [file_descriptor]

syscall

mov rax, r8

ret

read_file is just a label, a helpful convenience to let us identify where in our code flow to jump to. It’s basically a function, I told myself. You just jump to it when you need it, and jump away when you return. This is basically the same as a high level language. Nothing is that confusing. Ok, perhaps the documentation could be more straight forward but there are means and ways. Plus we have our handy bible if anything is that confusing.

Ok, so we’ll have to pre-populate the rdi register with the file path, not that different from passing in an argument. We wrangle some registers, make sure we’ve allocated memory elsewhere to put our data into, copy the data from the file to the memory, and then close the file. Then return. Look at that. Linux is doing most of the heavy lifting, and we were only moderately inconvenienced. Two hours in and we can read a file into memory. Maybe. We’re not actually sure anything is there, just that our code didn’t segfault or otherwise blow up. But hey, our compile command has elf64 in it, which must be a sign 4. We should probably print out our test file to make sure. There’s a syscall just for printing a file. Four lines of code. This assembly stuff isn’t so bad. A little tedious, but that’s why we’re reusing stuff.

A handful of syscalls, some memory management. There were a few register issues along the way, and perhaps a small detour to poking at things in Godbolt. (We’ll be seeing a lot of Godbolt). But hey, not bad for an early morning foray into assembly. I had even picked up the syntax on how to write comments.

So now all I need to do is write a for loop, make some conditionals, read a number, and call it good. I’m pretty sure that’s a one-liner in Mathematica and like maybe 5 lines of Ruby code. 20 if you’re verbose like I am. We just assign our current number to a register and… oh. Right. Each line is just raw bytes in memory. Just a giant long sequence of bytes, that we need to parse.

Ok, a bit monotonous, but doable.

Canto 2: The Limbo of ASCII

Here, as mine ear could note, no plaint was heard

Except of sighs, that made th’ eternal air

Tremble, not caus’d by tortures, but from grief 5

I’d already known that the file was going to be a collection of bytes. Everything in assembly is a collection of bytes. I hadn’t internalized what that actually meant in terms of parsing it into sane data types however. I let out a sigh, not caused by torture, but by eternal grief, as I realized I had three different problems to solve.

The first: line termination. In a higher level language, a simple “file.split(“\n”).each” would have given me a perfectly valid outer loop, and I could have gotten to work on each line. Here I’d need to process each line, character by character, until I reached a termination character (“\n”). Not the worst thing in the world, just a different way of thinking about things. That’s why I’d chosen assembly, to force me to think differently. Plus accumulators aren’t that new. We’d just need to look for the magic character 10 (which is 0x0A in bytecode), and that would indicate we should go to a new row. Easy. We can just do a comparison on the byte we’re on, and if it equals exactly ten, we’re at the end of the line and can do the logic on the number and direction we’ve already stored.

Logically it makes sense, there’s only three kinds of bytes here. Newlines, numbers, and either the letter L or R. Newlines tell us we’re done, L and R act as a directional signifier, and the number tells us how far to go. So if it’s not a newline or a L or R, we know we’re in a number. The L and R check is easy enough, if the byte we’re on equals either of those (and assembly helpfully accepts ‘R’ as a valid comparator input) we jump to some code to set a flag in a register to let us know what direction to go, and then jump onto the code to move onto the next byte. So far nothing alien to me. Oh the jumping around takes some thinking; after all, you just keep executing sequentially after a jump. The vaunted labels that looked like functions being only labels. But so long as you remember where you want to jump back to, and skip over the parts you don’t want to re-run, it’s all doable.

Which brings us to numbers. When we read the file, we read bytes. Bytes which point at an ASCII depiction of numbers, not actual numbers. For example, the character “1” is the byte 0x31. This is totally different from the number 1 which is 0x01 in bytes. If you try to add two characters, like say “1” + “1”, you can totally do that, it gives you 0x62 which is the letter ‘b’. Which can produce confusing results. Fortunately for us, all you need to do is remember to subtract 48 from the ASCII representation, and that gets you back to the numbers. In the ASCII standard, the character ‘0’ is stored as the byte value 48, so subtracting 48 shifts the symbols ‘0’–’9’ down to the actual integers 0–9. (which are stored literally in the digits 0-9).

Of course, it’s not as simple as that. Let’s take the number 123, which would be the bytes 0x31,0x32,0x33. We can only parse these sequentially, so we get 0x31, and subtract 48, and get 1, and then throw it in our register to store it. Then we hit the byte 0x32. We should probably store that in our accumulator too. So to do that we have to: multiply the current number in the accumulator by 10 (because 12 is 1*10 + 2) and then add the number we just read after translating it. We just keep doing that until we hit a non-number, and then we’re done.

Except of course, for once the code compiled without segfaults, the numbers were wildly incorrect. Not a problem, in a higher level language you’d set a debugger breakpoint, or just add a print line and call it good. In assembly we have to do things slightly differently.

print_number:

mov rax, rdi

mov rcx, 10

mov r8, print_buffer + 20

mov byte [print_buffer + 20], 10

convert_loop:

xor rdx, rdx

div rcx

add rdx, 48

dec r8

mov [r8], dl

cmp rax, 0

jne convert_loop

mov rax, 1

mov rdi, 1

mov rsi, r8

mov rdx, print_buffer + 21

sub rdx, r8

syscall

ret

A few iterations later and… huh. Our numbers are off by an order of magnitude. 68 becomes. 645. Weird. Almost like there’s an unexpected character. An hour of swearing later, (and one diaper change) and it turns out that before our newline there’s a 0x0D or a 13.

The math: 13 - 48 = -35. The result: 68 * 10 - 35 = 645.

13 happens to be the ASCII representation of \r. Windows strikes. A higher level language would have just known that in Windows newlines have a leading carriage return and I wouldn’t have to think about it. In assembly it cost me a weary sigh, and thirty minutes of debugging because of a convention that dates to the days of typewriters.

Canto 3: Lust for Registers.

A noise as of a sea in tempest torn

By warring winds. The stormy blast of hell

With restless fury drives the spirits on. 6

I am not going to take you through each problem day by day. Mostly because code blocks like this:

.gen_inner:

cmp r13, [num_points]

jge .gen_next_i

; Calculate distance squared between points i and j

mov rax, r12

imul rax, 24

mov r8, [points + rax] ; x1

mov r9, [points + rax + 8] ; y1

mov r10, [points + rax + 16] ; z1

mov rax, r13

imul rax, 24

mov r11, [points + rax] ; x2

mov rcx, [points + rax + 8] ; y2

mov rdx, [points + rax + 16] ; z2

; dx = x2 - x1

sub r11, r8

mov rax, r11

imul rax, r11

mov rbx, rax ; rbx = dist²

; dy = y2 - y1

sub rcx, r9

mov rax, rcx

imul rax, rcx

add rbx, rax

; dz = z2 - z1

sub rdx, r10

mov rax, rdx

imul rax, rdx

add rbx, rax

; Store pair: (dist², i, j)

mov rax, [pairs_ptr]

mov rcx, r15

imul rcx, 16

add rax, rcx

mov [rax], rbx ; distance²

mov [rax + 8], r12d ; i (32-bit)

mov [rax + 12], r13d ; j (32-bit)

inc r15

inc r13

jmp .gen_inner

Feel neither good to read, nor good to write. It’s me, clutching on to registers like a drowning man clinging to driftwood, not knowing what I’ll need and wanting to save everything. Even on Day 2, I was already churning through the code, wishing for abstraction where only raw bytes existed, hoping for functions when I had only labels, and wishing for someone to manage memory for me.

Because I noticed a terrible desire in me. A burning need. A need for registers. They were right there. Seducing me with their convenience. R8 through R15 whispered promises: we’re yours, no one has to know. Even on Day 2, I told myself it was fine. I had registers to spare. I’d clean it up later. I’d follow the conventions eventually.

I began to see the problem when I tried instructions like cmpsb. cmpsb, which stands for Compare String Byte. A very useful instruction which let me iterate over a string comparing values. So long as I set my registers correctly. So long as I gave it that space. Space which was valuable and limited. Still, on Day 2, it made sense to do it. I had registers to spare, all I had to do was move around some data. Who was I hurting?

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

check_block:

; Compare rbx bytes: [r9] vs [rdi]

push rcx ; Save your outer loop counter

push rdi ; Save your destination pointer

push rbx ; Save your pattern length

mov rsi, r9 ; Setup registers

mov rcx, rbx

repe cmpsb

pop rbx ; Restore them in reverse order

pop rdi

pop rcx

Still, I felt a feeling of impending doom. A nagging guilt. It was so easy. So tempting.. I’d seen registers get clobbered before. It wouldn’t happen to me. I had self control. It would be easy. By day 12, we had blocks like this:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

; From day12/day12.asm

solve_recursive:

push rbx

push rcx

push rdx

push r8

push r9

push r10

push r11

push r12

push r13

push r14

push r15

; ... do work ...

.solve_ret:

pop r15

pop r14

pop r13

pop r12

pop r11

pop r10

pop r9

pop r8

pop rdx

pop rcx

pop rbx

ret

All I wanted to do was save an int somewhere. Store a variable. A single line like int x = 10 was all I lusted for. Instead I had to keep my variables in the stack, remember the order, make sure they returned properly, and of course that we weren’t clobbering anything we needed. All to store a number, do a division or compare two bytes.

Canto 4: The Hungry Heap.

To strike him.” Then to me my guide: “O thou!

Who on the bridge among the crags dost sit

Low crouching, safely now to me return.” 7

Anyone who has ever studied up for interviews has had to memorize the difference between the stack and the heap. The reality is that the vast majority of the time, the heap is this magic thing that just works for you because you’re protected from it via abstractions. Like a regular commuter who doesn’t have to worry about the structures of the bridge he drives over. Unfortunately for me, as I ran out of hoarded registers, I needed more. More memory. More space. More places to put things. There was only one place to put it, the muddy, unclaimed territory of the heap. A morass of bits, hungrily waiting for me to try to build my crumbling edifices over it. The stack gives us a generous 8MB of storage. A fortune really, for most problems. But my appetite for memory grew day by day, and by Day 8 I needed more. There were too many pairs to store, too much information, and my appetite for data was only growing. I needed the heap, to hold my garbage. So like a beggar, I asked the system to please apportion me a tract. Somewhere to dump my miserable pile of bytes.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

mov rax, 9 ; The syscall number for mmap

xor rdi, rdi ; addr = NULL (We let the OS choose where the memory lives)

mov rsi, 16 * 500000 ; length = ~8MB

mov rdx, 3 ; PROT_READ | PROT_WRITE (We need to read and write to it)

mov r10, 0x22 ; MAP_PRIVATE | MAP_ANONYMOUS (It's just RAM, not a file)

mov r8, -1 ; fd = -1 (Required for MAP_ANONYMOUS)

xor r9, r9 ; offset = 0

syscall ; "Hey Kernel, give me the memory."

mov [pairs_ptr], rax ; The OS returns the address in RAX. We save it

But of course, it’s not as easy as merely taking the space. No, without abstractions, you can’t just call list[i]. You have to know the length of the data you’re storing, track the offsets and never, ever, lose track. If you lose track, you won’t know what you’ll fetch from the swamp of the heap. The formula is an easy Base + (Index * Element_Size) + Offset. So long as you do the math right and store the index (in a register) and the base, and the element size, and the offset, you can simply move along your array with no difficulty. I hope you don’t need to do anything like .find or .any because then you need to iterate over your entire array from scratch.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

; Calculate offset: i * 16

mov rax, [pairs_ptr]

mov rcx, r15 ; Index

imul rcx, 16 ; Element Size

add rax, rcx ; The Trek (Base + Offset)

mov [rax], rbx ; Finally placing the value

A constant cloying trek to fetch data that we’ve stored, unprotected by the umbrella of abstraction, motivated my unceasing appetite for more data. A deeper descent into madness.

Canto 5: The Hoarders of Hashmaps

Now canst thou, Son, behold the transient farce

Of goods that are committed unto Fortune,

For which the human race each other buffet. 8

If I would have traded hours for a simple let x = 10, what would I have traded for a map? For an O(1) lookup? For a quick node["you"] = "string"? I looked upon higher order languages with unfettered envy. Look at ruby creating a Node(‘foo’) without the user having to move a single register. The selfishness of python keeping it’s dicts, with their automatic compression and immediate lookup times to itself. I would have even taken a Java’s “treeified” HashMaps. I saw these languages, with their wealth of abstraction and seethed.

Where they had variables, I had registers, where they had abstractions I had the mud of the heap. But there is nothing like envy to spur a man on, so I would build my own abstractions. My own hashmaps. Mine. Mine. Mine. My data structures. Even if I had to first implement the code in python, and then translate it line by line, like a biological compiler, I needed them. All of them. Day 11 called for maps, and graphs and edges. Things that would only be one line in another language. But being poor in abstractions fueled me, honed me, it meant I wasn’t just going to build a dictionary. No, modern dicts are far separated from the hashtable and linked list implementations that interviewers love to talk about, we would build something suited to our specific needs. A poor mans dictionary, a bastardized implementation that would greedily store what I needed.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

; Get or create node index for name in edi (3-byte packed name)

get_or_create_node:

; ... (setup) ...

; Hash: simple modulo

mov eax, edi

xor edx, edx

mov ecx, HASH_SIZE

div ecx ; The "hash function" is just a raw DIV

mov ebx, edx ; ebx = hash bucket

; Linear probe to find or insert

.probe:

mov rax, [hash_table + rbx*8] ; Check the slot

cmp rax, -1

je .insert_new ; Empty? Grab it.

; Check if names match

mov ecx, [node_names + rax*4]

cmp ecx, r12d

je .found

; Collision - linear probe (The "Greedy" grab for the next slot)

inc ebx

cmp ebx, HASH_SIZE

jb .probe

xor ebx, ebx ; Wrap around if at end

jmp .probe

And since all I had was bytes, and bytes and bytes, my graph and its edges must be built upon them, an edifice of spite, aimed at the simple python solution that had taken me 30 minutes to put together.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

section .bss

MAX_NODES equ 1024

MAX_EDGES equ 32

; ...

adj_list: resq MAX_NODES * MAX_EDGES ; The graph is just a giant block of reserved bytes

adj_count: resq MAX_NODES ; We have to manually track the length of every list

If any node had more than 32 edges, everything would come crumbling down, but such are the risks of building upon the heap.

1

2

3

4

5

; Add edge: adj_list[source][count] = dest

mov rcx, [adj_count + r12*8] ; Get current neighbor count

imul rdi, r12, MAX_EDGES*8 ; Calculate Offset: Source_ID * 32 * 8 bytes

mov [adj_list + rdi + rcx*8], r13 ; Store destination at Base + Offset + Index

inc qword [adj_count + r12*8] ; Increment count manually

Brick upon brick, our tower rose. Part one fell behind us, as we rose to the dizzying heights of part 2. Where a simple cache[(node, visited_dac, visited_fft)] would have been the solution to all my problems. It would have let me handle the millions of visits to these two nodes. But instead of having a tuple, I had a bitmask.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

; Compute new state for neighbor

; state_new = state | (2 if neighbor==dac) | (1 if neighbor==fft)

mov rsi, r15 ; start with current state

cmp rdi, [dac_idx]

jne .check_fft

or rsi, 2 ; Manually set bit 1

.check_fft:

cmp rdi, [fft_idx]

jne .do_recurse

or rsi, 1 ; Manually set bit 0

1

2

3

4

5

; Cache result: index = node * 4 + state

mov rax, r12

shl rax, 2 ; Multiply node_idx by 4 (to make room for 4 states)

add rax, r15 ; Add the state (0-3)

mov [path_count + rax*8], r13 ; Store in the flattened array

I felt clever. A high-level language would have hashed the tuple (node, state), dealt with collisions, and allocated objects on the heap. But I knew something the compiler didn’t: my state space was bounded.

The state only had two booleans: visited_dac and visited_fft. Two bits. That meant only four possibilities. I realized I could implement a perfect hash, a collision-free mapping. I simply took the Node ID and shifted it left by two bits (multiplying by 4), effectively creating four dedicated slots in memory for every single node. No collisions, no probing, no overhead. Just raw, calculated offsets. It was the kind of optimization that makes you feel brilliant, right before you realize you forgot to zero-out the memory.

I had crushed the multidimensional complexity of the problem into a single, long line of memory. All I had to do was traverse the graph and update each state. Painful but nothing compared to the work to get our data structures working.

Canto 6: Rage Sort.

Fixed in the slime they say:

We were sullen in the sweet air that is gladdened by the sun,

bearing within ourselves the sluggish fume;

now we are sullen in the black mire. 9

Day 5 is a straight-forward range merging problem. You put your ranges in an array, sort them, iterate and merge, and out come your results. Normally I’d just call .sort on my array and maybe pass in a custom sort argument and be done. .sortin ruby uses quicksort, raw C code blazing through iterations. Or maybe I’d use sort_by which uses Schwartzian transforms, and I’d be 90% of the way there, and quickly too. (Not 100%, .sort can be slower if you pass in a custom block because it needs to translate between ruby and c a bunch, but in this case, with int primitives, it would be fast).

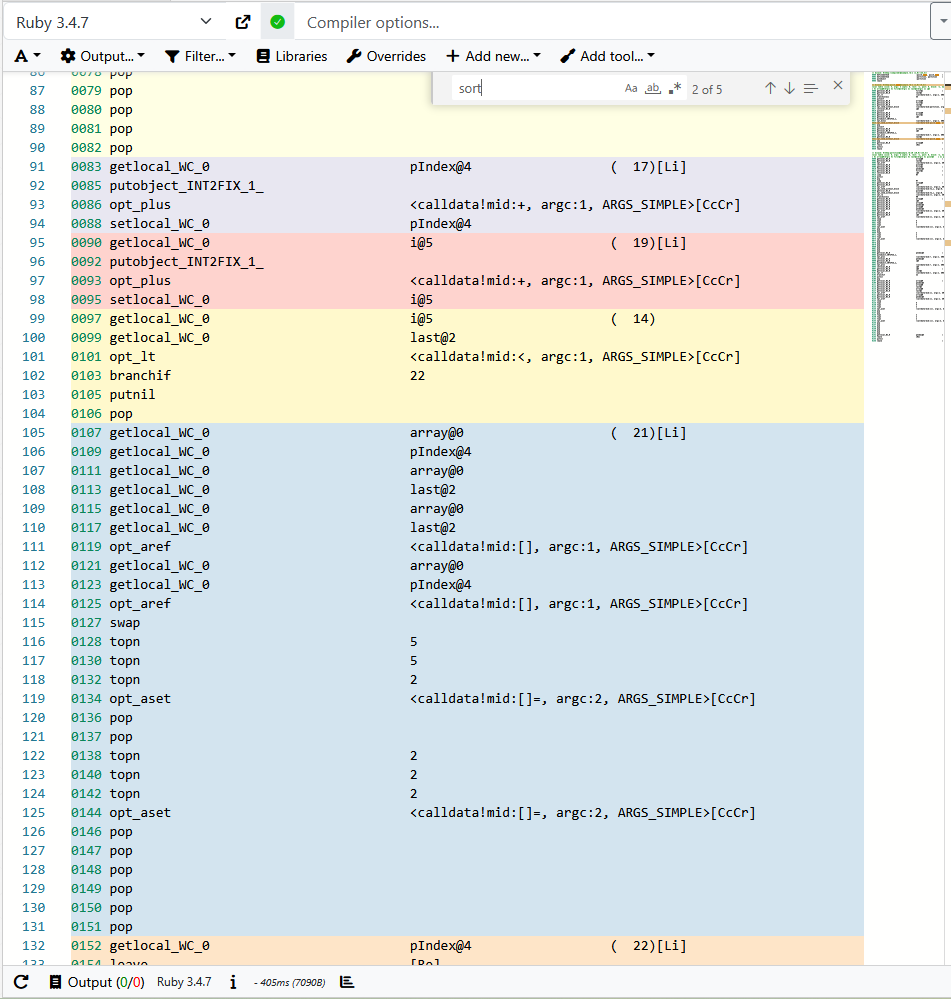

Here, I didn’t have the option of calling a cushy sort method. I looked at Godbolt, with Ruby’s sort_by and was given this:

1

2

3

0024 getlocal_WC_0 array@1 ( 4)[Li]

0026 send <calldata!mid:sort_by!, argc:0>, block in <compiled>

0029 pop

Thank you Godbolt. I’ll just call ruby’s virtual machine with sort_by! Why didn’t I think of that! But fine. Fine! Fine. I can implement quicksort in ruby and see what it looks like in Godbolt. How bad could it be?

My brain tried to understand it, and it slid off like it was a wall of sheer ice. Maybe it was because it was 4 am. Maybe its because I resented that I couldn’t just .sort. Maybe I was angry because I had finally realized what I had done to myself. Either way, I decided that I was going to implement the most basic sort possible.

I looked at the requirements for Quicksort: Recursion. Partitioning logic. Stack management. I looked at my energy levels. I decided I didn’t need speed. I needed violence.

I was just going to Bubblesort.

Bubblesort is the worst of the sorts. (Ok, not quite. Its O(n²). It’s two loops nested inside each other. It doesn’t ask you for a stack frame. It scoffs at your pivot index. Just two loops.

You walk down the line, looking at every pair of numbers. If the element on the left is bigger than the element on the right, you swap them. You do this over and over again until all the elements are in the correct order. It has all the algorithmic elegance of assembling furniture by duct taping it together. But it was a merciful 20 some lines, not 200.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

inner_loop:

cmp r9, r10

jge inner_done

; Compare ranges[r9].start vs ranges[r9+1].start

mov rax, r9

shl rax, 4 ; rax = r9 * 16

lea r11, [ranges + rax] ; r11 = &ranges[r9]

mov rcx, [r11] ; rcx = ranges[r9].start

mov rdx, [r11 + 16] ; rdx = ranges[r9+1].start

cmp rcx, rdx

jle no_swap

; Swap ranges[r9] and ranges[r9+1]

; Swap starts

mov [r11], rdx

mov [r11 + 16], rcx

; Swap ends

mov rcx, [r11 + 8]

mov rdx, [r11 + 24]

mov [r11 + 8], rdx

mov [r11 + 24], rcx

Just swapping. Over and over. A seeming endless churn of mud and violence. Thousands upon thousands of wasted cycles of repetition.

This is Rage Sort. There’s a better way. cargo build --release would have generated a vectorized Quicksort that runs in microseconds. But here I was, bleary eyed, in the mud, moving bytes one by one, punishing the silicon because I refused to cave in to languages that had things like a “standard library”.

It worked. It was slow, ugly, and offensive to computer science, but the ranges sorted themselves. The merge logic ran. The answer appeared. The rage subsided, replaced only by the hollow realization that I had just spent more than two hours doing what array.sort() does in 10 nanoseconds. All I had learned from wrestling in the mud was spite.

Canto 7: Heretical Visualization.

Well I ween he lives; and if, thus alone,

He seeks the valley dim ‘neath my control,

Necessity, not pleasure, leads him on. 10

Like Dante, the further I descended, the more horrified I became by what I saw. Unlike Dante, I didn’t get into Florentine politics, and worse, the sins were my own. Day 9 was it’s own layer of hell. The problem starts simply: put some coordinates on a grid, find the largest rectangle you can make with those coordinates. The logic to solve it was tedious, but not terrible. You just bludgeon the coordinates into submission by trying every single possible coordinate pair, and keeping the one that makes the biggest rectangle.

Part 2 on the other hand… part 2 has the fearsome eye

Part 2 simply asks you “find the largest rectangle… bounded by the coordinates we established earlier.” That is, if you would generate a rectangle and one of the points would fall in a region not bounded by the coordinates in our input, it’s not a valid rectangle.

Fine, you can just use ray casting. Draw a virtual ray from anywhere outside the polygon to your point and count how often it hits a side of the polygon. If the number of hits is even, it’s outside of the polygon, if it’s odd, it’s inside. (This is a classic in AoC problems)

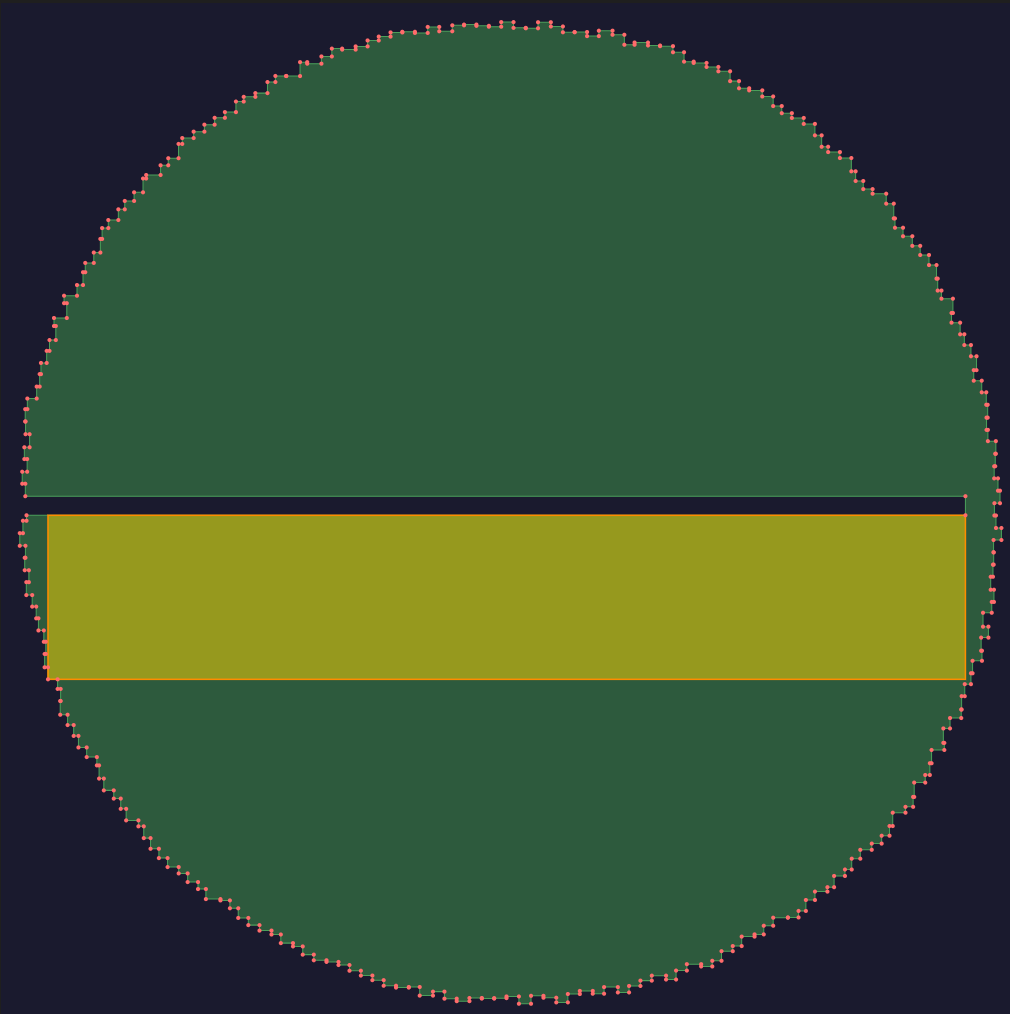

Easy. A couple of hours of putting assembly together, and you have a very reasonable solution. That just happens to be wrong. Over and over. In desperation I turned to claude, and asked “how do you visualize something too large for the terminal in assembly?” and it said, with all the innocence of the damned “You could build an SVG.” I shuddered at the thought. This was heresy. Hand rolled assembly is meant to be pure, bytes on bytes, movs, jmps, sub, not <svg xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg" viewBox="0 0 100000 100000">.

Three failed inputs later, I shook my fist at the heavens, and cursed the God that had abandoned me… And rolled down my sleeves and began to write code. An hour later, I had made an abomination, a horror, a monster:

1

2

3

4

5

6

mov rdi, circle_start

call print_string

mov rdi, [points + rax] ; x coord

call print_number_no_newline

mov rdi, circle_cy

call print_string

Things that should never be in your assembly code, viewBox. But what is an SVG if not just a giant string? And we understand strings now, even if they have to be manually closed tags and linebreaks.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

section .data

filename: db "../inputs/day9_input.txt", 0

svg_header:

db '<svg xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg" viewBox="0 0 100000 100000">', 10

db '<rect width="100000" height="100000" fill="#1a1a2e"/>', 10

db 0

polygon_start:

db '<polygon points="', 0

polygon_end:

db '" fill="#2d5a3d" stroke="#4a9f5a" stroke-width="100"/>', 10, 0

circle_start:

db '<circle cx="', 0

circle_cy:

db '" cy="', 0

circle_end:

db '" r="200" fill="#ff6b6b"/>', 10, 0

svg_footer:

db '</svg>', 10, 0

But it worked. I beheld my works and wept, for they had been for naught:

I could see why the rectangle was wrong. The rectangle was one pixel outside the bounded polygon. I had an off by one error.

An eternity to code the render, for a single measly error, but the problem was solved. All I’d had to do was sin against assembly itself.

Canto 8: To Kill and Butcher Math.

That this your art as far as possible

Follows, as the disciple doth the master;

So that your art is, as it were, God’s grandchild. 11

If you have not had to look up floating point numbers in Intel’s intrinsics guide at two in the morning, reeking of still drying baby formula on your shirt, you have not known the rage that makes you want to strike down math itself.

That’s where I found myself in day10 . Part 2 asked a simple question: given a set of button behaviors, find the least number of presses to meet a specific pattern. I may have learned very little linear algebra (much to my eternal shame), but gaussian elimination has come up enough times that I immediately recognized the category of problem. This is usually the part of Advent of Code where I pivot to python, import numpy and do some LU decomposition and pat myself on the back.

So it was with trepidation that I opened google and searched around for implementations of gaussian elimination in python, and put them into Godbolt. I was not heartened by what I saw. I would need floating point numbers.

In a civilized language, or even civilized assembly, you would use Floating Point numbers. The x86-64 processor has an entire unit dedicated to this, the FPU, with its beautiful xmm registers and single-instruction division. It is the natural order of things.

I looked at the documentation, considered learning a whole new set of tools, and instead chose violence.

I refused to learn how the vector registers worked. I decided that if the FPU wouldn’t help me, I didn’t need it. I would simply… Implement rational number arithmetic from scratch using integer registers. Looking back, I assume some form of madness possessed me, that I had decided to take a cleaver to mathematics itself.

The code I wrote was not “elegant”. It was not “good”.

You cannot just divide A by B. No, you have to track the numerator and the denominator separately on the stack. To add two numbers, you don’t just add. You have to cross-multiply the denominators, add the numerators, and then, by the mercy of an uncaring God, simplify the result.

I spent four hours writing an Euclidean GCD (Greatest Common Divisor) algorithm by hand.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

.gcd_loop:

test rcx, rcx

jz .gcd_done

xor rdx, rdx

div rcx

mov rax, rcx

mov rcx, rdx

jmp .gcd_loop

.gcd_done:

mov rdi, rax

pop rbx

pop rcx

jmp .find_gcd_next

I split numbers with ruthless efficiency, not caring how many I cut down. Every single row operation in the matrix meant dragging these integers through the mud. I ground through them, one at the time.

I made one optimistic comment, at the beginning, that stands as a bitter irony to the carnage I inflicted

1

2

3

; Copy matrix to work area (use fractions: num/denom pairs)

; We'll work with scaled integers, multiplying by LCM when needed

; For simplicity, keep matrix as integers and track denominators

Simple indeed. All our code did was, for each single row:

- Find a non-zero pivot in the current column

- Swap rows to bring pivot up

- Eliminate that column in all other rows via row operations

- Reduce each row by GCD to prevent integer overflow

- Identify free variables

- For each depending on the free variables:

- If there are no free vars: Unique solution. Back-substitute and sum the button presses.

- Check divisibility (must be integers) and non-negativity.

- 1-3 free vars: Brute force enumerate all values from 0 to max_target, compute the implied basic variables, keep the minimum valid sum.

- 4+ free vars: Give up

- Return the required minimum amount of button presses

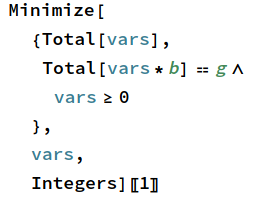

In mathematica the solution looked like this

To call this carnage is to undersell it. I had stared blankly at result after result for hours. I had captured all the essence of the seventh circle of hell. Violence against myself. Violence against Dave, whose one line mathematica solution had mocked me, and who was forced to hear my endless complaints, and violence against nature itself.

Canto 9: The Hypocrite’s Descent

A painted people there below we found

Who went around with footsteps very slow

Weeping, and in their looks subdued and weary 12

Dear readers, I have hinted at this, I have suggested it, but I’ll go right out and say it. For many parts of this exercise, I was not really writing assembly. Not anymore. I was just a human transpiler. I’d start by confidently thinking I’d solve it purely in assembly. That today I’d be able to effectively debug it. When my answers were wildly off, that was doable, I knew the answer to day 2 was not, in fact -20000000, though I might not be clear at how I arrived at the number. The problem was when, like on day 9, the number was temptingly, alluringly close, but I was met with “your answer was too high! Try again in one minute, or check out these resources”.

Resources which sneered at me, because they assumed you had not chosen to walk the path of damnation, that you weren’t clad in a lead robe painted in gold, like the hypocrites in Dante’s Malebolge.

So day after day I’d run into some intractable bug, and I’d be forced to write a bunch of code in a higher level language to even solve the problem, sometimes somewhat grotesque code, written as quickly as possible, and then translate parts of it into assembly, line by line, like a poor imitation of a superior computer. Perhaps this meant I didn’t think like an assembly developer. That I failed to appreciate the strength and beauty of the language. That I had squandered an opportunity by staring at my ruby implementation and spending hours asking claude to please explain why that instruction worked the way it did, and could it maybe suggest a better way to do the thing that was taking 27 lines of code? By day 11 however, I had come to terms with it. I was going to finish this, I was going to escape this hell, the only way I knew how, through the final layer.

Nothing could have prepared me for what awaited me there.

Canto 10: The Beast In The Ice.

I did not die, and yet I lost life’s breath:

Imagine for yourself what I became,

Deprived at once of both the life and death. 13

I looked at the problem for Day 12, and considered quitting then and there. A packing problem. You’d think I’d be an expert at those. Traditionally you solve this thing with a recursive DFS. Not trivial to implement, but it’s not the first time it’s come up in AoC. If you were particularly ambitious, dancing links are a great option here. As I looked at it, I saw the immutable pile of blocks, the wealth of edge cases I’d likely run into. The plan was conceptually simple.

- Find the first empty cell

- Try all pieces in all orientations

- Check and verify the fits.

- Call yourself again to find the next empty cell

- Backtrack

It sounds so easy. Just recurse. In Python, it would be. The language creates a stack frame, it protects your variables, it remembers where you came from. It is a loving, caring parent holding your hand.

In Assembly, the stack is waiting to corrupt your results and make you question your sanity. To “call yourself,” you don’t just jump. You have to save the universe. Because registers are global, if you change r12 in the deep recursion, r12 is changed forever. So before you dare step down into the next layer of the ice, you must manually preserve your sanity, register by register. Every recursion opened with

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

solve_recursive:

push rbx

push rcx

push rdx

push r8

push r9

push r10

push r11

push r12

push r13

push r14

push r15

Of course there’s the backtracking. Oh, the backtracking. You can’t just return False. You have to clean up your mess. You have to manually lift the piece. Manually increment the counter. Manually restore the registers. A simulation of a high-level language running, manually performing the job of a compiler stack frame allocator.

But that doesn’t scratch the surface. The reason this took me almost three days is because every time my code would fail, I’d be forced to figure out an example case, and then write a minimal version of it, by comparing, line by line, against my python results. I could feel myself sinking into the ice, buffeted by the gusts of each edge case, desperate to reach the end. Calling them edge cases is generous, some of my bugs were simply bugs, failing to stack pieces, rotating them out of bounds but still counting them, overwriting variables I should not override, returning too early. Basic, basic bugs.

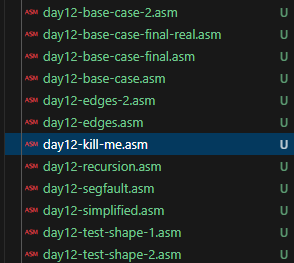

I wound up with 23 files between edge cases and small tinkering assembly examples. Each minimal case, each attempt at solving a small part of the problem felt like an endless breathtaking descent, step by step, barely holding on. Each time I hoped this was the one, the last edge case, that finally I was out of hell. Each time I saw a cheerful “your answer is too low!” or it failed to match my python implementation.

I cannot count the number of times I forgot to ret or I forgot where I was reting to, or I saw an impossible result or a segfault because I had, of course, failed to clean up a register somewhere.

I’m not proud of my day 12 code. When I submitted it I didn’t feel like I’d achieved something, I felt, quite literally, like I’d escaped a hell of my own making. That I was finally free. That I no longer had to look at mov judging me for my sins against assembly. What I learned, if anything, is that we take a lot for granted. That we use so many tools and conveniences, and that stripped of them, even the most simple of operations is a battle to the death. I’ll never complain about the borrow checker again, because it keeps me from producing yet another segfault because I wandered into the wrong part of memory.

More fundamentally, I learned that abstraction isn’t just convenience. It’s a forgetting mechanism. It’s what lets you not-think about register allocation so you can think about rectangle packing.

When I wrote Python first and then translated line by line, I wasn’t solving the problem slowly. I was trying to be both compiler and programmer. I was trying to reason about graph traversal while manually shuffling bytes into registers. I had to do them serially because they couldn’t fit in my head at the same time. Just as with computers, my working memory is finite. When it’s occupied by “r12 has the loop counter, rcx will get clobbered by div, I need to preserve it, where did I put the base pointer” there’s no room left for “what’s the recursive structure of this packing problem?” The registers don’t make Advent of Code harder. They replace Advent of Code with a different problem entirely: how to do even the most basic of operations. Every layer of abstraction is a compromise, you surrender control and trust the language to take care of recursion, memory management, what have you, so you can actually think about the problem.

Strip the abstraction away and you discover the real shape of hell. It’s not that the work is tedious. It’s that it captures your attention so completely that the problem you came to solve becomes unreachable. The torment isn’t the registers. The torment is that the registers are all you can see. You can’t reason about DFS because you have to worry about which register to mov. Sometimes an abstraction is bad because it unintentionally adds a cost you didn’t expect. Most of the time it’s just saving you from the hubris of thinking you can hold everything in your head, all at once.

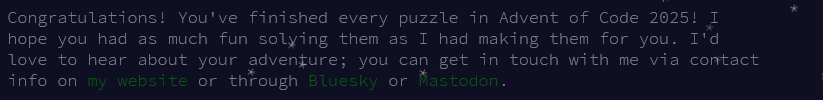

Like Dante, I do not plan to ever return to hell. Unlike Dante, I don’t have to make my way through purgatory or deal with the controversy of “the sick woman” of Florence. Instead as I submitted part 2, wrapping up Advent of Code, I looked out the window at the softly falling snow, and turned on the heater to fight back the chill.

Then I began to install Pyanodons Hard Mode for Factorio, and wondered if this was how Dante felt, finally looking up at the stars.

Not all of these are 100% the translation I used, unfortunately John Ciardi’s excellent translation is not freely available online in text form (that i could find), so the links are not 100% accurate, wherever possible I prefered the more readable Ciardi version, but not always. ↩

If you want to listen to one of the better translations of Dante’s Inferno, you can do worse than John Ciardi ↩

The command of course being the super simple

nasm -f elf64 common/utils.asm -o common/utils.o && nasm -f elf64 day02/day2.asm -o day02/day2.o && ld common/utils.o day02/day2.o -o day02/day2 && ./day02/day2Which, after deciphering once, I ran slavishly since and it worked fine. ↩Inferno, Canto XXIII ↩

Inferno, Canto XXXIV ↩