Trackmania I - The History of Machine Learning in Trackmania

The Goal

Trackmania (2020) is a racing game, created by Nadeo and released by Ubisoft, in which players drive a car from a start to a finish through a fixed number of checkpoints, and aim to do so as quickly as possible. The largest regular event in the game is Cup of the Day (CotD), in which several thousand players are given fifteen minutes to learn a map and set the fastest time they can. Divisions are created based on the best times recorded by each player, with Division 1 hosting the fastest 64 players, Division 2 hosting the next fastest 64, and so on. Within each division, players race on the track for multiple rounds, and the slowest players each round get eliminated. The last man standing wins the division, and the winner of Division 1 wins that Cup of the Day.

CotD has an excellent format and tests all aspects of skill in Trackmania: discovery, optimization, and consistency:

- Discovery: Players have to learn a new map, and have to quickly intuit the correct angles and speeds for each new turn; there’s simply not enough time, in fifteen minutes, to try all possible strategies and combinations.

- Optimization: Players have to take risks and and fail frequently during the qualifying round, and know when to continue with an attempt (to learn more about the map) and when to reset (to save time); it’s easy to keep resetting in the hopes of getting a perfect start, and never learn the rest of the map.

- Consistency: Players, once in a division, have to drive consistently for up to 23 rounds in a row to win, and one mistake can cost the whole match: you don’t have to win any round except the final round, but if you ever lose a round, you’re out.

Winning CotD means that you have mastered multiple aspects of the game. But we want to go quite a bit further than that.

Our goal is to create a program that can, with no prior experience on the map, win the qualifier and every individual round of Division 1 of Trackmania’s Cup of the Day.

The Motive

Machine learning, as of 2024, is dominated by techniques which require absolutely massive amounts of data and processing time in order to return human-level outputs. AlphaZero played itself for 23 million games to achieve superhuman performance at Chess; the image generation model StableDiffusion was trained on a dataset of 2.3 billion images; GPT-4 is rumored to have cost $100 million for ~20 yottaFLOPs to pre-train. Amateurs and hobbyists have attempted many open-source replications of all the major commercial machine learning models, and have had a fair amount of success, but they tend to be improvements or tweaks on existing models, using techniques like quantization to speed up and compress a model that already exists. Even our own previous attempt at machine learning, getting the world record in HATETRIS, ended up requiring the evaluation of hundreds of billions of moves, and most of our progress throughout the project came from creating faster and faster emulators to make those hundreds of billions of moves achievable on a single PC.

But not everything we might want to learn has endless amounts of training data available, and not everyone who might want to learn it has endless amounts of computing power at hand. Like the HATETRIS project, we want to see if state-of-the-art machine learning techniques can be implemented by amateurs on a single computer to achieve nontrivial goals. But unlike the HATETRIS project, we want to try this in an area where we can’t download or generate unlimited amounts of data.

Trackmania Nations Forever (the predecessor to Trackmania 2020, released in 2008) has a TAS tool called TMInterface, which allows for custom speed modification (playing the game dozens of times faster or slower than normal), save states, input playback, and much more besides. It’s a fantastic tool, and has led to a boom in TMNF TAS runs…but it’s not what we have in mind, and it’s why we’re not playing on TMNF. We want a program that can not just play the game like a human can: we want a program that can learn the game like a human can. Fifteen minutes to get a world-class time on a brand-new map, playing at one second per second. And we want to do it on one desktop PC.

The Players

It wouldn’t be a proper race if we were the only competitors. As of the start of 2024, there are eight people or groups who have made - and published - programs that can play Trackmania autonomously. Numerous others - Lelaurance on TM2020 and Louis De Oliveira on TMNF and ooshkar on TM2020, to name three - have reported some amount of progress, but have not published enough for us to know exactly what they’ve done or how far they’ve gotten by doing it. So, as we stand on the starting line, let’s see how much of a head start each of the other racers have.

Rottaca

“Convolutional Neural Network drives in Trackmania Nations”, by Rottaca.

“Convolutional Neural Network drives in Trackmania Nations”, by Rottaca.

The earliest attempt we know of at a self-driving car in Trackmania was from 2017, by a German software developer named Andreas Rottach (going by Rottaca), who published the code on GitHub. The idea was supervised learning: take examples of cars driving well, take screenshots throughout the game, label the screenshots with the keys (left, right, or neither) which were being hit at that moment, and train the network to hit the appropriate key when given the appropriate screenshot.

With a dataset of 100,000 images - equivalent to roughly a few hours’ worth of driving at ten frames per second - and with no concept of momentum or even any ability to use the brakes, it’s not surprising that the car eventually flipped out of the track and crashed during the test run. Still, the program was clearly able to distinguish between left turns, right turns, and straightaways. The architecture Rottaca used - a convolutional neural network - was good enough to learn at least some of the important features of the game, just by looking at static pictures of gameplay.

TMRL

Learning from existing gameplay is nice, but even better is unsupervised learning, so that the program can teach itself without needing human guidance on whether or not a given program is good. To that end, Yann Bouteiller and Edouard Geze, from the Polytechnique Montréal in Canada, created not just a single program but a full unsupervised learning pipeline for Trackmania 2020, called TMRL. Like Rottaca, Yann and Eduoard created a convolutional neural network to parse input data - but this time, without directly training that network from human runs. Instead, a single human run was done to create a reference trajectory to create rough estimates of where the track was and where the car needed to go. The car drove on its own, and was rewarded based on how much of the track it covered in a given amount of time.

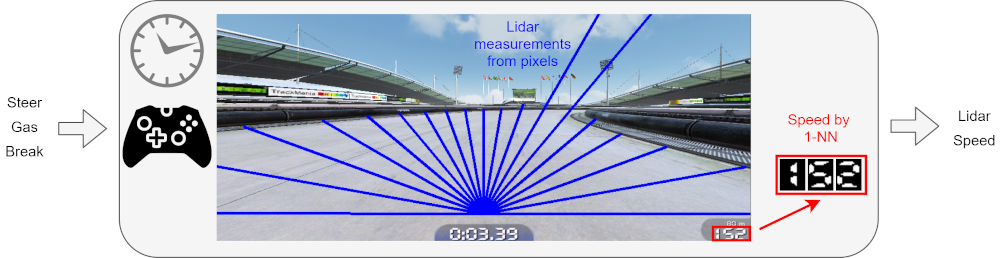

There’s a lot of raw data on screen to process, though, and processing that data takes a lot of time. So, in addition to a single static image (and an option to include up to three previous screenshots), TMRL also includes a LIDAR environment. Instead of the network needing to process the entire screenshot of the entire game, the screenshot is reduced to 19 numbers, and each number represents the number of pixels between the center of the screen and the road border, from a different angle. While this restricts the program to flat tracks which always have the car on a standard road, with visible borders, it allows for much faster neural networks and much better response times, which is important when trying to develop and improve everything else.

The LIDAR environment in TMRL, from the TMRL GitHub page.

The LIDAR environment in TMRL, from the TMRL GitHub page.

And in the spirit of human-computer rivalry, Mr. Bouteiller and Mr. Geze were featured on the French show Underscore_, in which their program - trained for 200 hours in the LIDAR environment - competed on a track against professional players. To quote the results:

Spoiler: our policy lost by far (expectedly 😄); the superhuman target was set to about 32s on the tmrl-test track, while the trained policy had a mean performance of about 45.5s.

Not exactly superhuman performance, quite yet - but certainly better than playing randomly, or smashing into walls. And while their Trackmania Roborace League has not yet gotten much traction, the framework they created was built on and improved on by others.

Laurens Neinders

The first was Laurens Neinders, from the University of Twente in the Netherlands. In February of 2023, he published a paper titled “Improving Trackmania Reinforcement Learning Performance: A Comparison of Sophy and Trackmania AI” as his Bachelor’s thesis in computer science. In order to understand Trackmania, Mr. Neinders studied a program from a different game entirely: “Sophy”, which in 2021 achieved defeated humans in an exhibition match of the racing game Grand Turismo Sport. The program didn’t achieve fully superhuman performance in the game - the exhibition match did not have tyre or fuel management, among other things, while the full game does - but defeating humans even in a limited match was far beyond what TMRL had been able to do. So, what was the difference?

Nienders concluded that this was due to the difference in the information available. Sophy had information about the track curvature of the upcoming 6 seconds of track, based on the current speed. TMRL, however, only had distance measurements from the LIDAR. While the TMRL program could plan for the next turn, it could not plan two turns ahead, and this fundamentally limited the program to mere safe driving, avoiding walls and crashes, but never optimizing.

The LIDAR environment in TMRL, vs. the distance curvature measurement in Sophy, from Neinder’s paper.

The LIDAR environment in TMRL, vs. the distance curvature measurement in Sophy, from Neinder’s paper.

So, he implemented that same track curvature lookahead in Trackmania. By driving a track and using LIDAR measurements to find the track edges, he created a pair of Bezier curves representing the two borders of the track, and then trained the neural network to take a segment of that curve as the input for the car.

The result? Improvement! Ignoring shortcuts - because the tmrl-test track can be shortcut - the program came close to the final time of an average player on the track, though still almost four seconds away from Gwen’s record on the track, set during the Underscore_ exhibition match in 2022 linked above. Neinders proved that, given track information, programs can learn to not just not crash, but actively plan ahead beyond what’s immediately visible, and find good racing lines across multiple turns.

| Racer | TMRL | Neinders | Average Human | Best Human |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time (s) | 44.413 | 38.402 | 36.985 | 34.308 |

AndrejGobeX

Programmer AndrejGobeX, from Slovenia, also built off the TMRL library, but improved it in a different direction. Where Neinders added track curvature lookahead, AndrejGobeX kept the LIDAR-type input, but changed the learning algorithm. Andrej used both supervised learning - like Rottaca five years earlier - and the Soft Actor-Critic Model that TMRL used, as well as implementing a genetic algorithm called NEAT (without much success), the Proximal Policy Optimization algorithm, and the Twin-Delayed Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (TD3) algorithm.

| Track | Human | SAC | PPO | TD3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nascar2 | 14.348 | 16.180 | 19.126 | 16.247 |

| Test2 | 12.728 | 14.109 | 14.174 | 17.894 |

| Night | 10.124 | 10.576 | 10.668 | 10.728 |

Results were mixed. SAC had the best performance overall, with PPO and TD3 alternating second and third place, but all three were far from Andrej’s own personal bests for the tracks he tested them on. However, the additions he made to the pipeline were so effective that Andrej was no longer bound by the limits of video games, and the program successfully drove an RC car down a walking path at full speed.

RC car driven by the supervised ‘Maniack’ network, by AndrejGobeX

RC car driven by the supervised ‘Maniack’ network, by AndrejGobeX

Going outside and interacting with the real world was an impressive achievement, and one probably too difficult for us to match; for this project, we’re going to stick with playing Trackmania.

PedroAI

Thus far, every attempt at training a Trackmania-playing program has trained the program on one map at a time. As a result, no matter how well the network did on one track, it would have to be retrained - probably significantly retrained - to perform well on any other track. PedroAI, who managed to get the incredible URL ‘trackmania.ai’, wanted something much more general. He didn’t want a program that could play a map. He wanted a program that could play any map.

A Trackmania program training on three maps simultaneously, from PedroAITM’s Twitch page.

A Trackmania program training on three maps simultaneously, from PedroAITM’s Twitch page.

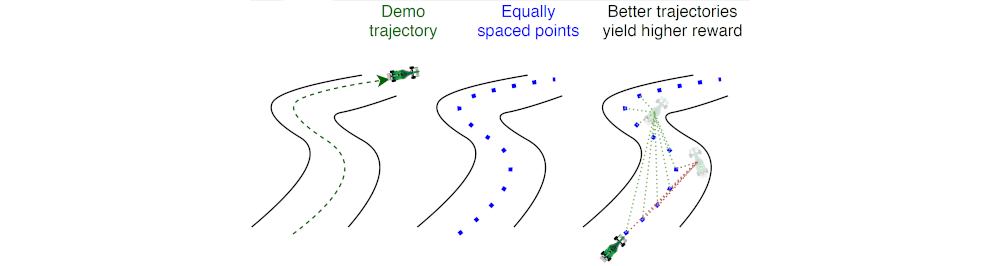

Using deep Q-learning, PedroAI set up an impressive training loop. Three collector agents drive tracks, using a neural network with the game state (both the current screenshot and data such as position and velocity) as the input, and produces an output estimating the total reward the car is expected to experience throughout the rest of the run for each possible keystroke. The reward being the speed of the car at each moment (a tenth of a second) in the direction of a reference human-driven trajectory, plus a bonus for actually reaching the finish line.

Of course, the network can’t actually know for sure what the car’s speed will be for the entire rest of the map. But, as the three collector agents drive tracks, making estimates and gathering experiences, a fourth training agent looks at past game states, examines how much reward the training agent actually got in reality, and trains the network to better approximate that amount. And after playing through each track ten times, the collector agents switch to three new tracks, and after another ten attempts, switch to three more. And after going through several hundred maps from previous campaigns, the cycle starts all over again.

Results so far have been mixed. With knowledge of the reference trajectories, the network was able to play significantly better than random moves; in the longest training cycle to date, the program was able to finish all 100 maps in the white and blue difficulties from 2020 to 2022, and get 11 author medals and 49 additional gold medals out of those hundred maps. This took 169 days of training to achieve, which in and of itself wasn’t too bad - except that the average completion for almost all maps was still worse than the bronze medal, even if the sum of best completions was getting to the level of a passable Trackmania amateur. And the training for almost all maps had flattened out - after half a year of practice, the program wasn’t improving any further.

But, even though the training has thus far consistently plateaued on all the various attempts at and tweaks of training, PedroAI proved that the concept of a generalized Trackmania-playing program can work. A neural network can play better than randomly across more than a hundred tracks. His program is the best covered thus far, and as of the start of 2024 remains by far the best generalized Trackmania-playing program.

Bluemax666

However, there are three people or groups who have shown the potential of how well a program can do on an individual track.

The earliest, in 2019, was a French programmer named Bluemax666, who was inspired by a 2017 project in Python to play the game Grand Theft Auto V. He started the way many did: a simple program that could only accelerate and not brake, using a black-and-white bitmap of a small section of the screen, and converting manual keystrokes to virtual joystick inputs. But that’s not where he stopped.

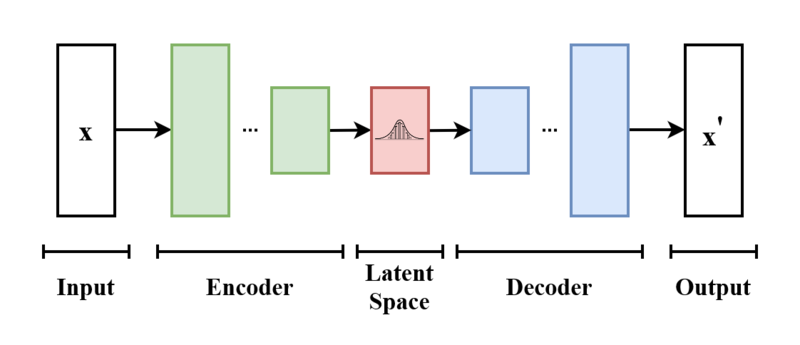

A year later, he released a new program, with very different implementations to what everyone else had done. Instead of processing the image with LIDAR or with convolutions, he processed it with a technique known as Variational Auto-Encoding. Resizing the screenshots to be 64x64 allowed him to not only store the images in color, but also to provide the last eight frames into a neural network, rather than just the most recent frame by itself; this got a program almost to a gold medal on a three-lap endurance track, stymied only by a bad reward value. By 2021, he had moved to TM2020, where his program could come within 0.3 seconds of the world record on a training map, without access to any game information besides the screen and the car speed - no information about gear, about surfaces, tire contact, acceleration, or even where on the map it was.

A view of the latent variables and the reconstructed screen from Bluemax666’s “Trackmania AI after 48 hours of training on ice (Reinforcement learning)”.

A view of the latent variables and the reconstructed screen from Bluemax666’s “Trackmania AI after 48 hours of training on ice (Reinforcement learning)”.

While others before and since used the Soft Actor-Critic model, nobody else has done it quite the same way. Variational Auto-encoding in particular is a fascinating method that takes input (in this case, a screenshot of the game), reduces that input to a small handful of variables, called “latent variables”, and then tries to use those variables to reconstruct the original input as closely as possible. The better the reconstruction, the more accurate those variables are at representing the important features of the input. If the rconstruction was perfect, that means the latent variables capture everything important about the original image, and a neural network with those latent variables as inputs will have all the information that the full image could possibly give them, for a tiny fraction of the processing time.

A basic overview of a variational auto-encoder, taken from the Wikipedia article here.

A basic overview of a variational auto-encoder, taken from the Wikipedia article here.

Bluemax666 eventually set aside the project, having achieved what was (in 2021) the best results in Trackmania machine learning for both TM2 and (in limited test tracks) TM2020; results that were competitive with human amateurs. Over the next two years, two others would take the next step forward, getting results not just competitive with human amateurs, but better altogether.

Yosh

Of all the people to have attempted Trackmania machine learning over the years, Yosh has been the single most persistent. Back in May of 2020, he started out with the most basic autonomous Trackmania program: pure randomness. Three thousand cars bounced around a custom Kacky-type map at random, hitting random keys and going in random trajectories. But the resulting montage and flood of airborne cars wasn’t the goal - the goal was to test out a method of controlling the car from a program. And so, a month later, he released the first of many videos on the subject, titled “AI plays Trackmania”.

Yosh has tried almost everything that everybody else has. His first attempt had a simple bilayer neural network, but subsequent attempts used a genetic algorithm (NEAT) (like AndrejGobeX) and Deep Q-learning (like PedroAI) and Soft Actor-Critic (like Bluemax666 and TMRL); the program uses a system like LIDAR, but with more information about the upcoming curvature of the map (as proposed by Laurens Neinders); the program even started off not allowed to brake, like Rottaca’s all the way back in 2017. Aside from image recognition, he has tried a bewildering variety of techniques and strategies, and along the way has come up with an idea that showed a great deal of promise for future attempts.

Yosh’s network looks at the vast reward rising in the distance, and contemplates how best to get the carrot and avoid the stick. From “Training an unbeatable AI in Trackmania”.

Yosh’s network looks at the vast reward rising in the distance, and contemplates how best to get the carrot and avoid the stick. From “Training an unbeatable AI in Trackmania”.

A common technique in Trackmania tech maps is called the “neo-slide”, which allows momentum to be preserved around corners, even at low speeds. It’s essential to playing tech maps (maps with lots of sharp angles and turns, played significantly below the car’s top speed and top gear) at a high level, and it’s not difficult for a human to learn when told how. However, the specific sequence of inputs - full steer, then stop steering a split second, then start steering again while holding the brakes - is quite difficult for a network to learn a priori, as doing it badly is worse than not doing it at all. Yosh realized that the network had almost certainly tried neo-slides randomly during its hundreds of hours of playing, but didn’t ‘know’ that neo-slides were worth doing in the first place, and had no reason to ‘remember’ how to do them when it randomly tried it.

To solve this, Yosh introduced what we’ll call the training wheels technique: he gave the network a high reward at the start for doing a neo-slide, whether it helped or not, and then once the network had mastered the neo-slide, removed the reward. Since the network now knew how to neo-slide, it at first continued doing neo-slides all the time, as it had been doing. But, as the changed rewards started to filter through, the network gradually stopped using neo-slides where they didn’t help gain more reward, and kept using them only where they actually helped.

In general, incorporating expert knowledge into the network, by hand, is close to impossible. But incorporating expert knowledge into the reward function is completely feasible. Yosh demonstrated that expert knowledge can be introduced to teach the network what to do, and then removed once the network ‘understands’ it. This hints at broader guidelines for training Trackmania programs. The world record for TMNF’s A01 Race requires two “speedslides”, both of which are just on the verge of impossible (since speedslides are harder to gain time with the slower you are, and below 400 speed can’t gain any time no matter what). A program whose only experience with Trackmania was A01 Race would have a very difficult time discovering those two speedslides by itself. But, if the program started by training on fullspeed maps where speedslides are much easier to discover, and then transferred to A01 Race, it would likely have a much easier time.

Yosh described his program as ‘unbeatable’, because he himself could not beat the program on any of the three maps he trained it on. Various players quickly found shortcuts for all three maps, since none of the maps had intermediate checkpoints, but pro caster Wirtual decided to beat the network on the simplest map, without shortcuts. The network’s best time was 29.00 seconds. It took Wirtual over ten hours to beat the network’s run with a 28.98, even though Wirtual had spent over ten thousand hours learning the game to a professional level. So the network was, if not ‘unbeatable’, then still extremely impressive, the most impressive network yet covered.

But the next day, another project announced a time, for that same track, half a second faster than either.

Linesight

The Linesight project, on Trackmania Nations Forever, is at the start of 2024 the most advanced Trackmania machine learning project made public. Using a convolutional neural network to interpret the screen as a 160x120 greyscale image, and with a small twist on the by-now standard reward function (the distance traveled along a reference trajectory over the next seven seconds), the network is able to train on any map, with no preprogrammed knowledge of track curvature or geometry.

With that kind of generality, the Linesight developers did not want to merely run their program on custom-built tutorial tracks. They wanted a challenge. And the challenge that presented itself was ESL-Hockolicious, a map created in 2008 that has since become one of the most hunted maps in all of TMNF. One minute long, ludicrously optimized, with a variety of tricks, turns, and jumps: anybody, whether human or machine, who got a good time on this map, would need a broad understanding of tech maps and low-speed maneuvering in Trackmania. So, how well did the program do?

The Linesight program’s progress over eighty hours of training on Hockolicious. From “Trackmania AI Learns To Drift and Beat Pros ? | Hockolicious”.

The Linesight program’s progress over eighty hours of training on Hockolicious. From “Trackmania AI Learns To Drift and Beat Pros ? | Hockolicious”.

After eighty hours of training (training at 9x speed, so roughly a month of equivalent playing for a human player), the program achieved a time of 54.06, a time not achieved by human players until the map was six years old. This placed it at what would be (in the no-shorctuts category) a tie for 20th place on the global leaderboard - out of millions of attempts by thousands of skilled racers, in a map far from trivial to set a good time in. The Linesight project proved that reinforcement learning can get nearly professional-level performance on real maps. And, as we enter the scene in 2024, that is the state-of-the-art.

Us

Of course, we come into this with modest ambitions: make humans obsolete in the process of racing Trackmania. Perhaps we’ll be featured in the cover of a scientific journal to show how AI now dominates all racing sports. The kind of thing we can reasonably expect when entering a project with no directly relevant experience.

Obviously, logically, we know that this kind of oversized ambition isn’t realistic. No one at Google is going to see this and say “They really do need eight billion dollars in cloud credits for the noble task of racing emulated cars.” But having ludicrous ambitions is a key aspect for avoiding the thing that kills most projects: ennui. For us, if a project is merely aiming to be “kind of good” then it’s not going to go anywhere, because being “kind of good” is not exciting. So we trick our brains: we envision the realistic best case scenario (a pretty good racing program) and multiply it by a thousand. Is it grounded? No. But when you’re spending eight hours trying to figure out how to configure virtual desktops over ssh, you need something to keep you going. When every block you put down is a step towards a towering edifice, setbacks feel smaller, and wins feel like they’re worth something more.

So, that’s always been how we approach the early days of these projects, with unrealistic goals that we “know” are impossible. Once its potential starts to materialize, once you have the shape of the work laid down, then you can start to discard the grandiose for the grounded, and then you can start to take those castles in the clouds and boil them down into the bricks of the house. Projects like this are a long haul. We’ve already spent four full months trying to get TM2020 and OpenPlanet both installed. If you don’t have a good goal, you won’t have a reason to make it off the starting line.

Series

Comments powered by giscus.